I received some interesting responses to the notes I wrote this week about Halloween and its history. If you didn’t see the one that started it all, you can do so by visiting here: https://cruciformstuff.com/2025/10/27/is-halloween-a-pagan-holiday/.

For the record, I’d say my essential premise was not necessarily about being for or against observing the holiday, but rather that many Christians seemed more than willing to simply surrender the event to the secular world entirely, having somehow been taught that it wasn’t the Church’s to begin with—that it was a pagan holiday that the Church tried to baptize. And yet, in truth, it’s really the other way around. Halloween came from the Church’s sanctified imagination and was later hijacked by paganism. It was Christian, but then it was emptied of its Christian meaning and filled with the world’s nonsense.

That right there—the hollowing out of something holy until only the shell remains—maybe that’s the more critical point. I say that because it describes far more than just All Hallows’ Eve. It’s a pattern for our age.

In other words, we live in a world that memorializes things but forgets the reason we memorialize them in the first place. We still hang lights at Christmas, but fewer folks seem to remember that Christ, the light of the world, is the reason for those lights. We still gather for weddings, but we do so assuming that marriage is humanity’s idea. It isn’t. God started it. It was His idea. Nevertheless, holy spaces are exchanged for thematic wedding venues, and favorite rock songs replace sacred hymnody that proclaims marriage’s sanctity. I suppose even beyond the Church’s doors, we celebrate plenty of other civic holidays we no longer understand. Plenty have told me they appreciate Memorial Day, not for its solemn character, but because it extends their weekend.

All around us, the forms remain, but the meanings are gone.

But this is how the world works. It doesn’t always destroy. Sometimes it rewrites in order to repurpose. It keeps the rituals but drains them of their truth. It keeps the beauty but forgets beauty’s essence.

Here’s my concern. It sure seems like Christians are more often tempted to retreat in these situations. Overwhelmed by how corrupt something has become, rather than fight to take it back, they figure the only possible solution is to surrender the field and move on. I know folks who won’t wear a rainbow on their clothes because LGBTQ Inc. has hijacked the symbol.

But God’s people own that symbol. It’s ours. Still, it seems we’re more inclined to surrender it than reclaim it.

That’s precisely how we lost Halloween. And it’s how we’re losing nearly everything else.

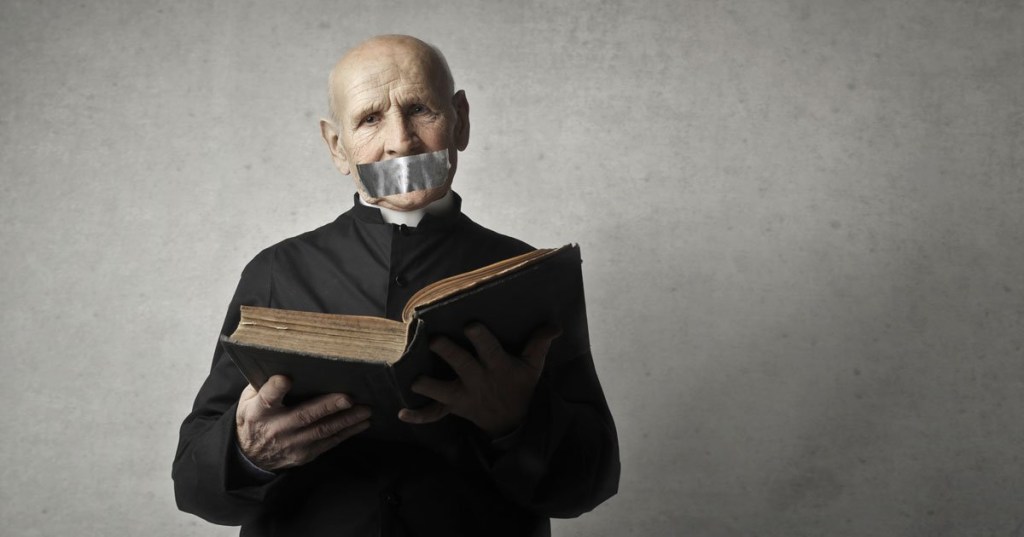

For the record, one of the clearest places to see this is in worship. Somewhere along the line, the Church decided that the way to reach the world was to mimic it—that the key to filling the pews was to empty the sanctuary of everything that made it sacred. And in the process, the Church’s worship—its highest demonstration of theology—was rebranded as a form of evangelistic enticement, something meant to attract rather than feed. But that’s never been worship’s purpose. Worship’s purpose is not to entertain the unbeliever or to market the faith (Ecclesiastes 5:1-3; John 4:23–24; Galatians 1:10), but to carry Christians into a place where time and eternity meet—where God tends to His people personally, giving them the gifts of forgiveness that sustain them (Ezekiel 34: 11-16; Matthew 26:26–28; Luke 24:30–32; 1 John 1:9; Revelation 7:9–12).

The tragic irony is that in chasing cultural appeal, we lost something the world needs from us: transcendence. When the Church stops sounding like the Church and starts echoing the culture, she ceases to be a holy and distinct refuge from the noise.

But again, this isn’t merely about worship styles. It isn’t even a critique of instruments or melodies. It’s about forgetting where these good and holy things came from in the first place. The world borrows and bends what it never built. The world didn’t invent most of what it claims to have invented. It didn’t invent marriage. It didn’t invent human sexuality. It didn’t invent justice. It didn’t invent what’s beautiful. It didn’t invent charity. It didn’t invent education. All of these things are fruits from God’s soil, and as a result, are, by right, crops to be harvested from Christianity’s garden. I was just talking with a dear friend this past Tuesday about how the university itself began in cathedrals. It was a place to learn truth as an extension of God. Now the very institutions that exist because of the Church’s intellectual legacy would rather burn incense to the self and its ideologies than bow the knee to the actual Truth made flesh that made their existence possible.

Or take art. I shared with that same friend how the world still paints, sings, sculpts, and builds. But holy moly, it sure seems like it no longer knows why. For example, while walking on the treadmill recently, I was watching a documentary about the 80s band Devo. Essentially, the band members claimed to be a consolidation of art, music, film, and social commentary. At one point in the movie, a founding member noted how one of their goals was to rid the world of Christian influence. Then an audio clip from an early interview played. That same bandmate could be heard saying, “We never said we were opposed to the Church. We just said we’d rather have cancer than Christianity.”

I didn’t keep watching for much longer. It struck me that music, something meant to elevate the soul, is so easily wielded by the culture as a weapon to offend that same soul. Art, which once imitated divine order and beauty, is now used to desecrate. Masterpieces are defaced. Blasphemy is called boldness. Ugliness is praised as authenticity. Chaos is paraded as radical creativity. For me, these are just proofs that when God is removed from something, it doesn’t become better or, as some would insist, freer. It becomes grotesque.

Now, I don’t want to wander too far here, so I suppose part of my point is that anything emptied of holiness can only go in one direction. It can only collapse into mockery. This trajectory worsens wherever Christians give up ground in retreat.

And by the way, when I used the term “paganism” before, I didn’t mean people dancing around in robes in the woods performing animal sacrifices. I meant a worldview that cannot stand true transcendence. Paganism, ancient or modern, is really just an older name for what we now call secularism. Secularism is paganism in modern clothes. That said, it’ll forever be the same naked humanity trying to exist in creation apart from its Creator.

And that, I think, is why Christians must be very selective when counting their losses and choosing retreat. Every time the world steals something sacred—every time it hollows out what was ours and paints it in its own colors—our response shouldn’t necessarily be to abandon it. We should first consider how to reclaim and refill it. We should labor to turn the world back to what it once knew.

Marriage belongs to God, and so we do what we can to turn the world toward that truth. Life belongs to God, and so we head to the front lines intent on taking back that ground. Beauty, truth, and everything else I mentioned already belong to Him. And even when the world tries to rewrite the definitions, it can’t escape the reality that every good thing it holds remains a gift from a gracious Lord who “gives daily bread to everyone without our prayers, even to all evil people,” as Luther explains in the Fourth Petition of the Lord’s Prayer in his Small Catechism.

So, thinking back on what I wrote earlier this week about Halloween, maybe the appropriate follow-up question isn’t, “How did Halloween become what it has become?” Perhaps we should be asking, “Why do we continue to let the world steal all our stuff?”

Yes, the world has a way of spoiling things. Still, I tend to think that Christianity has a remarkable ability to let that happen. But there’s another, even better ability we possess. We have been empowered to re-sanctify what the world spoils. I mean, if we can take a cross—a dreadful device of torture and death—and put it into our sanctuaries as a foundational symbol of Christianity itself, we can figure out how to snatch back the rainbow from the LGBTQ mafia. I’d say we can even go wandering through the darkness on a cool October night dressed like a scary monster, all the while laughing in the devil’s face as we take back All Hallows Eve.

That’s our heritage—to reclaim, to remind, to re-infuse the sacred into what’s been stripped bare. Because in the end, the world can only paganize what God first sanctified. And if that’s true, then the call to the Christian forces shouldn’t be “Retreat!” but rather “Charge!” And by God’s grace, it’ll be ours to capture and reclaim.

Holy Week is upon us. God’s plan has been exacted.

Holy Week is upon us. God’s plan has been exacted. It’s very early, 5:30am to be precise. I’m writing this note from Cantrall, Illinois. Again, to be precise, I’m at Camp CILCA, which is just outside of Springfield.

It’s very early, 5:30am to be precise. I’m writing this note from Cantrall, Illinois. Again, to be precise, I’m at Camp CILCA, which is just outside of Springfield.