If you haven’t already heard, the U.S. military used our country’s infamous bunker-buster bombs yesterday to take out Iran’s nuclear sites. Whether one agrees with the decision or not, it’s a sobering reminder: the world our children are navigating is growing more perilous by the hour. That said, when I woke up this morning, I had already intended to write about a significant role reversal I experienced last week. I’m going to stay the course, yet I can already sense how this morning’s news will impact it.

Essentially, my daughter, Madeline, recently earned her private pilot’s license. As a Father’s Day gift, she took me on an hour-long flight. We departed from Bishop International Airport in Flint, flew to a small airstrip in Linden, landed and launched twice, and then returned to Flint. On approach into Flint, she performed a maneuver called a “slip.” I looked it up and found the following definition to be exactly as I experienced:

“A slip is an aeronautical maneuver that involves banking the aircraft into the wind and using opposite rudder to maintain a desired flight path while increasing descent rate or correcting for wind drift.”

In plain terms, Madeline banked us left, and yet, we didn’t turn. We slid sideways while descending rapidly. Just above the runway, she finally straightened the plane, leveled us out, and touched down as if we were angels gently descending from heaven.

She was amazing.

Now, I started by saying I experienced a significant role reversal. To frame all of this in the proper perspective, it really wasn’t all that long ago that Madeline’s life was in my hands in every way imaginable. Indeed, it’s as if only recently, I was tucking her into a car seat and securing the five-point harness, even adjusting the straps to fit her comfortably while ensuring maximum safety. I was the one who checked twice—sometimes three times—that every latch was secure, every buckle snug, because that’s what a father does to keep his child safe. He does things like hold her hand in public. He hovers behind her on staircases that she is still too small to climb. He steadies the handlebars on her first bike ride, jogging alongside her down the sidewalk, ready to catch her when she tips. Everything about her very existence—the entirety of her well-being—is entrusted to him.

But last Sunday—Father’s Day, no less—somewhere just beneath the clouds, the roles reversed, and I found my life was entirely in my daughter’s hands. I climbed into the copilot’s seat and fastened the belt, which she then refastened because I hadn’t done it correctly. She proceeded to adjust it accordingly. And then she was the one now glancing over the vehicle’s every dial, confirming each setting, running her hand along the controls, reciting the pre-flight checklist items with unbroken concentration. I did nothing. She captained the headset, talked with the towers, and guided me through what to expect.

I guess what I’m saying is that the magnitude of that transfer wasn’t lost on me. It was exhilarating, yes, but also profoundly humbling.

Still beaming a couple of days after the flight, while Madeline and I were driving together, I told her again how proud I was of her. I mentioned a quote that had resurfaced in my mind as we flew—something from C.S. Lewis’ The Four Loves. He wrote so profoundly, “To love at all is to be vulnerable.” I explained how placing my life in her hands had revealed something. It wasn’t just that I trusted her. It was more about the depth of love I have for her, the kind that knows just how much she loves me, too.

I’ve known Lewis’ words for a long time. I’ve reflected on them in the context of marriage, friendship, pastoral ministry, and countless other situations where love demands a certain measure of risk. But I’d never thought to apply them to my kids until now. And yet, there they were, soaring right beside us at 2,000 feet on Father’s Day.

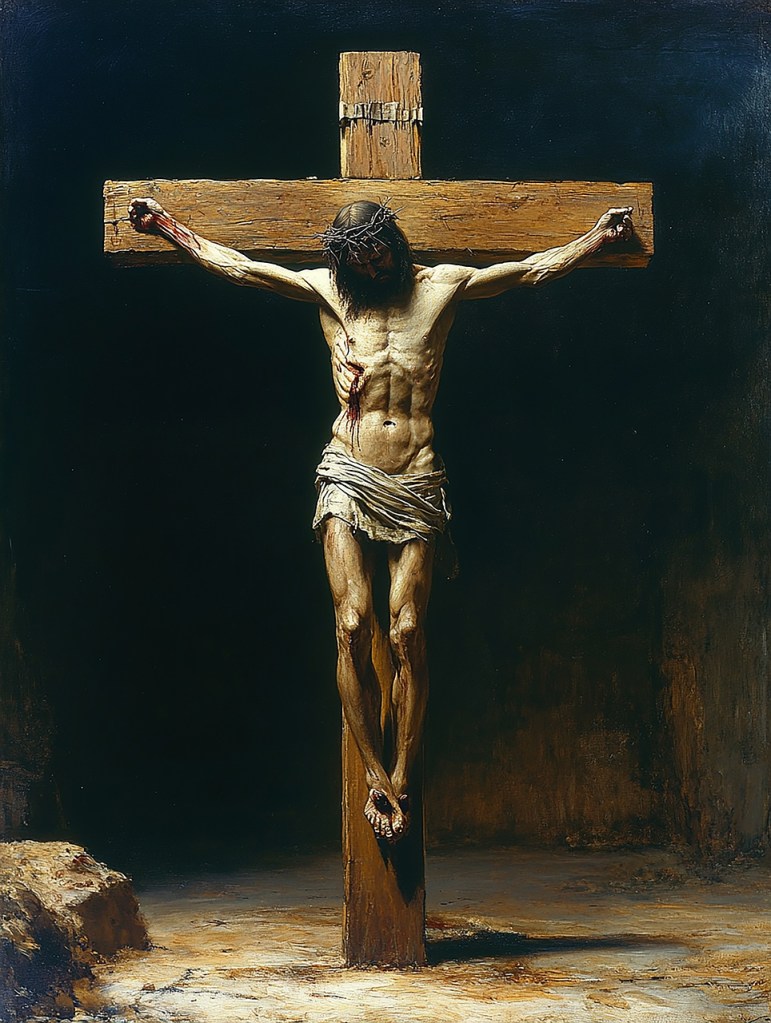

I’m usually pretty good with words. But this morning, I’m feeling somewhat limited. The English language doesn’t really have the capacity for genuinely communicating the moment your parental life shifts from giving care to receiving it—from being the one at the controls, both literally and metaphorically, and then, in an instant, letting go of the illusion that I would always be the one doing the work to keep my child safe. That kind of vulnerability doesn’t come easily, especially for a dad. But it is, I think, a place where, if we’re looking through the lens of the Gospel, God shows us just how complete love can be in a family.

I suppose something else comes to mind in all of this, too.

I would imagine that most Christians are familiar with the text of Proverbs 22:6, which reads, “Train up a child in the way he should go; even when he is old, he will not depart from it.” Most folks see that verse in terms of instruction in moral grounding and right living. That’s not wrong. But it misses the heart of the verse.

Its primary aim is that we would raise our children in the “way,” namely, faith so that when they do climb into the cockpit of life, so to speak, they do so not only with competence but with wings outstretched for trust in Christ. In that sense, Proverbs 22:6 reminds us that even as our children’s hands might reach to ours for learning character, skills, and such, it is far more critical that they know to reach for the Lord’s hand in all things. Only then can they truly navigate both the clear skies and the storms with spiritual wisdom and poise. Only in Christ will they know how to take off, how to “slip” when necessary, and how to land with grace.

Anyone considering these things honestly will recognize something more.

Without question, the world my children are navigating is by no means the same one I inherited. Long before the latest news about Iran, the skies they were flying in were already far more turbulent. The voices buzzing through the coms are more confusing, almost unintelligible. The instrument panel in front of them, while more advanced, is almost entirely calibrated by a secular age that denies God’s existence altogether, calling His Word foolishness and insisting that truth itself should be wholly despised.

My point is that the role of Christian parenting cannot be passive in any of this. It cannot be content merely with getting one’s kid into a good college so that they are materially successful. All of that ends when they breathe their last. As I’ve often said from the pulpit, this world and everything in it carries an expiration date. You may not see it, but it’s there. That said, we are not just raising children to exist and survive among temporal things. We are raising them, as Luther said, “to believe, to live, to pray, to suffer, and to die” (LW, Vol. 47, pp. 52-53), which, by default, means we’re raising them to exist in this world with eternal things in mind. We’re raising them to stand, to speak, and to boldly hold the line when others around them are folding. We’re raising them to do these things, not with arrogance, but with conviction formed by the eternal Word of God.

That’s why Proverbs 22:6 matters so deeply. Indeed, to “train up a child in the way he should go” means to help position them for good character and success. But the “way” it mentions is not abstract. It is the cruciform road that leads through repentance and faith in Jesus. When we train our children in this way, we’re grounding them in the very mind and heart of God.

And they need this grounding. They’re already being told that truth is subjective and that steadfast Christian conviction is cruelty. Worst of all, the surrounding world insists that biblical godliness is an artifact of a bygone era. They are surrounded by cultural winds that do not merely blow—they howl. If they are to fly straight—if they are to correct for this world’s drift—they will need spiritual discernment. They will need courage calibrated by sound doctrine and faithful practice. They will need to be taught to see everything in this world through the lens of who they are in Jesus.

In a sense, the time has already come for me to realize that my kids are now flying and I’m not. If you haven’t yet arrived at the same realization, then just know that you’ll be there soon enough. The time is coming when your little ones’ hands will be on the controls, and your hands will be folded in prayer.

That time comes sooner than we think. Parents, the preparation begins now.

When the choice is between faithfulness to Christ and the world’s distractions, choose faithfulness, even when the child doesn’t want to. Lead the way. Even as they might kick and scream to get free from the car seat, strap them in and set out. Do this not only because you’re teaching them how to fly but why to fly. Do this, remembering your children will one day be at the controls, and they’ll be faced with circumstances you never imagined.

Still, when this happens, you’ll be okay, even if things appear to be going south. You’ll be confident that you did everything possible to keep them connected to Christ. You’ll be able to hope that, when it matters most, they’ll know to lean not on the wisdom of this world but on the One who will never steer them wrong. Even better, you’ll know that even though you’re not in the cockpit, Christ is, and regardless of what anyone’s bumper sticker might say, He’s no copilot.