For starters, as a clergyman, I knew I’d take some heat for the book. I knew those scenes of extreme vigilante violence—moments when a man in a clerical collar arrives to erase the most vicious among us—I knew this would send some spinning into a fever.

Honestly, I’ve really only read one critical sentence about the book from an advanced reader, and the expressed observation didn’t surprise me. He noted something I did intentionally. Beyond this, it seems most folks, once they picked up the book, couldn’t put it down until they finished it.

Nevertheless, two individuals reached out to me privately with concerns. While separate, their concerns were essentially the same. I’ll attempt to paraphrase their thoughts. But before I do, you should know the book’s premise.

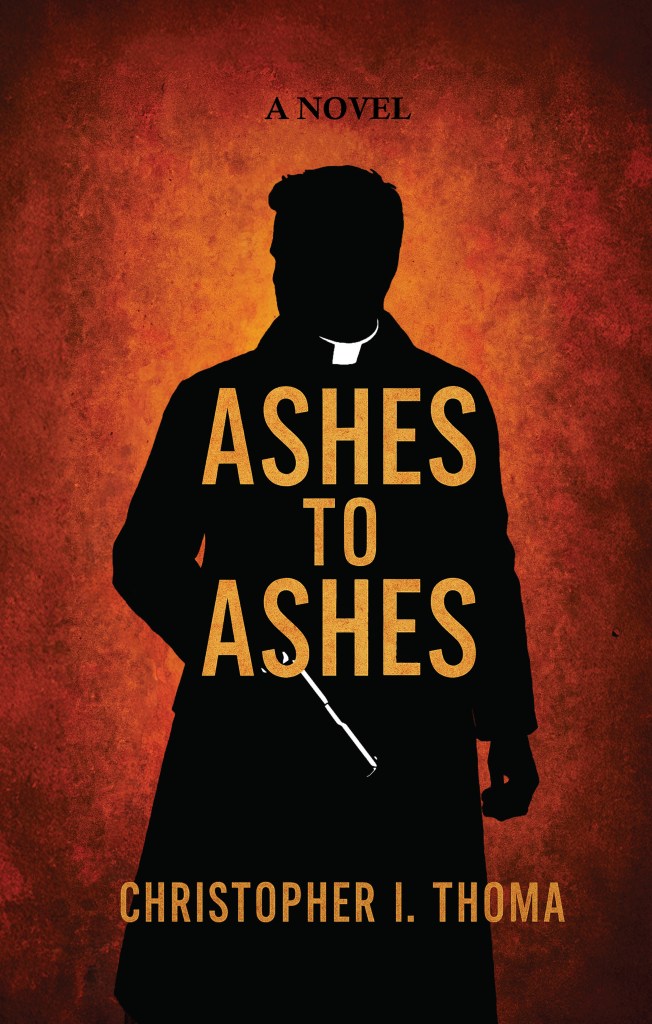

Essentially, Ashes to Ashes follows Reverend Daniel Michaels, a small-town Lutheran pastor who, while visiting one of his members, is somehow knocked unconscious, and when he awakens, he finds the church member dead. From there, the story steers toward a human trafficking network operating under the cover of a nearby church-run women’s shelter. With the possibility of law enforcement being compromised and the guilty hiding in positions of authority—right out in plain sight—Daniel shoulders the unbearable burden of both grief and responsibility. What follows is a harrowing descent into vigilante justice—brutal in every way—scenes as messy as they are decisive. Daniel wages war against predators in their homes, alleys, and shady motels, each encounter leaving more blood on his clerical collar than before. However, threaded through the brutality is a much deeper conflict. I won’t reveal too much, except to say the novel builds inexorably toward a pile-up collision between repentance, vengeance, vocation, hope, redemption, damnation, right and wrong, Law and Gospel, ultimately leaving readers scorched along the way by some of the best narrative writing I think I’ve ever produced in my entire life.

Seriously. I’m so proud of this book. I immersed myself in Reverend Daniel Michaels’ world, and I employed every ounce of my creative faculties to bring the reader into it, too.

All of this said, and to paraphrase a concern: “Isn’t it dangerous to put a clergyman that close to this stuff? It seems unbecoming of a guy like you to write something this.”

I hear the concern. The question is serious. It deserves a serious reply.

First, take note that there’s no swearing in the book. Also, no sex or nudity. There is one scene in which an abused girl is noted as naked, and yet, Reverend Michaels, after he deals with the man in the room abusing her, and before he moves on to other rooms with the same fury, he covers her up, brushes her blood-stained hair, and tells her she’s going to be okay. His gentleness with the victims is markedly profound. He cares.

Second, admittedly, there is gore. And yet, the book isn’t about glorifying the results of a pastor’s rage. It’s about putting vocation into the most severe of circumstances—into the refiner’s fire—and watching what burns away, and what does not.

If you felt a shiver reading that, good. You were meant to. The book is a meditation on the threshold of talk and action—the proximity of hero to villain, prayer to fury, genuine justice to unbridled vengeance. Daniel prays before and after; the words are “always crisp.” And yet the soundtrack in his head is Johnny Cash’s The Man Comes Around, a cracked, apocalyptic psalm about a God who, whether or not we want Him to, does, in fact, come around. And He chooses how He’ll do it.

So, how does He use us in the process? Where do we fit in? The book never lets the reader relax into easy answers, because the context isn’t easy.

In one of the two messages I received, I was told I “put the man in the collar too near the sword.” That comment was referring to Romans 13—the government’s bearing of the sword.

My reply: Yes, I did—and on purpose. Not to baptize vigilantism, but to force an honest Christian reading of Romans 12 and 13. Paul’s words are prescriptive, not descriptive. And so, what does that mean exactly in a world where “the powers that be” can be both God’s servants for good and, at times, participants in harm. For example, when a nation sanctifies the slaughter of its own unborn children, that is not righteousness—it is evil dressed in legality. Evil doesn’t become less monstrous because it is legal or convenient. It remains blood crying from the ground (Genesis 4:10), and the Church’s unwillingness to confront it makes us complicit in the very silence that lets it thrive.

There’s a funeral sermon in the novel that walks that blade’s edge aloud. Daniel proclaims, “‘Vengeance is mine,’ saith the Lord, ‘I will repay,’” then warns that we too often hear the verse only as comfort for victims and not as a warning to the evildoers. And so, Daniel preaches, “Do not mistake God’s patience for apathy… He will act.”

But, again, what’s our role?

Whatever the answer, you’ll notice in that same sermon—in the same breath—Daniel wrestles himself back to the Gospel’s center. He preaches the Lamb who ultimately bears vengeance in His own body so that sinners might become sons and daughters. We are transformed into those who can take action when action is required.

If, while you’re reading the book, you feel the tension in these things, then the story’s doing precisely what it’s supposed to be doing. I refused to rest in the cheap catharsis of tidy judgment or pious quietism, both of which are a pestilence in the Christian Church today. Instead, I chose to walk Daniel straight into the furnace and keep him there until the sparks started flying and you, the reader, flinched.

Ashes to Ashes isn’t tidy, because life isn’t tidy. Evil certainly isn’t. It’s raw, relentless, and sometimes terrifyingly close to home.

And so, in this world’s darkest pages, what must we bring to moments like these?

One of the comments I received was that in the moments of confrontation, Reverend Michaels offers no grace to the villains. I suppose I’d ask, is grace the appropriate first response in every situation? I’m one to say no. Hopefully, there’d be time for grace in any normal situation. But first, evil needs to be subdued and the victims protected. Unfortunately, sometimes that means making a mess. Sometimes that mess is bloody, and the villains ultimately lose out on grace’s opportunity.

Another comment said straightforwardly that this book “could scandalize the weak.” That concern is baked into the book’s DNA. The dedication page itself anticipates readers who’ll “see autobiography where none exists.” In the end, it’s fiction, though painfully plausible fiction, and if a reader can’t figure that out, they probably shouldn’t be reading it to begin with. Also, it is not a sermon in disguise. In fact, the story risks discomfort precisely to protect Christian preaching from naïveté. In other words, keep it simple, and remember: if we will not name evil, no matter its form, our sermons deserve to be taken less seriously by those in the pews who’ve likely already experienced what we refuse to see.

Another paraphrased comment: “It valorizes anger.” No. It interrogates it. Daniel’s anger is understandable, but it is also corrosive; he knows “refinement and ruin come from the same flame.” His most powerful moments are not when his fist is clenched and the Colt 1911 is raised to judge, but when his conscience is pierced. He is repeatedly pulled back to his calling, to the Gospel, even as judgment drums in his ears. The novel’s best question isn’t “How far will he go?” but “What will the fire leave behind when it’s done with him?”

If someone reads Ashes to Ashes and comes away thinking, “Pastors should punch harder,” then they read carelessly. The arc is faithfulness-shaped: a parade of revelations that corner the reader with the same double-bind that corners Daniel—do something and don’t become someone else while you do it. In that corner, you discover why he wears the collar while doing what he does. It’s not to bless sin, not to cosplay a crusader, but first, to let the demons know who’s coming for them; and second, to do everything he can to hold on to who he is—to Whom he belongs—when the room is filling with smoke.

I suppose I should add my own concerns at this point.

If anything, the Church needs two kinds of courage right now. It requires the courage to be clear and the courage to act. Mercy without either of these leaves victims unprotected. It turns us into the thing we hate. In a little town—Linden, Michigan—a place that smells like spring and looks “peaceful and quiet,” evil was buying time and gaining strength because the only thing opposing it were people wearing piety’s mask of politeness. The book tears the mask off and demands that the Church, and I suppose, all of society, look in the mirror.

It demands, “Do something. Stop sitting idly by and do something.”

So, to those who wrote to me with worried words: I’m with you in the worry. You should know I wrote Ashes to Ashes to earn that worry—not to dismiss it. But I’m also asking you to step into the furnace with me for close to four hundred pages. Watch what burns. Watch what stubbornly will not. And when you’re done, preach Christ crucified like it matters for victims and perpetrators alike. Then go to the altar and receive what we cannot manufacture: genuine mercy that doesn’t blink in the face of horror, and the holiness that can stand and act in any circumstance without losing one’s soul along the way.

If you want a copy, visit https://www.amazon.com/Ashes-Christopher-I-Thoma/dp/1955355053/.