Before Jennifer and I were married almost 28 years ago, we attended pre-marital counseling sessions with our pastor. Rev. Dr. Jon Vieker conducted them. I was serving alongside him as his DCE (Director of Christian Education) at St. Mark Lutheran Church in West Bloomfield, Michigan, at the time. On occasion, Jennifer recalls a question he asked during one of the sessions. It went something like, “Do you sometimes feel like Chris’s personality is different among the congregation than it is when it’s just the two of you?”

Thankfully, Jennifer declared with confidence, “Not at all!” Interestingly, I think she remembers that question more than the others because she gets asked similar questions by folks here at Our Savior in Hartland, Michigan. They want to know if the guy in the pulpit and at the front of the Bible study class is the same around the dinner table or changing a tire on his Jeep. When the question is posed again, thankfully, her answer remains the same today. Although I’m guessing it sounds a little more like, “He’s still the same doofus in public that he is in private.”

Admittedly, every relationship has its nuances. Unique personality traits emerge among close friends and remain subdued among first-time acquaintances. Still, there’s nothing more troubling than knowing a person’s truest self, only to see it transform into something completely different when others are around.

I know people who are this way, and it bothers me more than most. In my own circles, I know a pastor who is well-beloved as a theologian and scholar, and yet, behind closed doors, he’s the first to break confidences and share every dreadful detail about others he does not like. I know a public figure who carries the same prestige before crowds, and yet, in private messages or by phone, he is unendurably condescending, as though he’s the parent and I am the child.

I know everyone is flawed. This is true because everyone is thoroughly infected by sin. I certainly know I fit into the “everyone” designation. Nevertheless, if I were to categorize everyday human dreadfulnesses, I’d put habitual duplicity near the top of my list of off-putting flaws. A duplicitous person is incredibly hard to trust.

This is true because you can never be sure the version you’re experiencing is real—or worse, if any of the versions actually are. This kind of shifting personality can cause others to walk on eggshells, constantly second-guessing conversations and motivations. It’s difficult to build meaningful relationships with someone who wears different personas depending on the audience. Why is this? Because integrity, which is little more than honesty and consistency stirred together, is the bedrock of trust. Without this, suspicion can take root. Concerning the pastor I mentioned, I sometimes wonder: Regardless of what he says to me in friendly conversation, is the moment genuine, and if not, then what is he saying about me when I’m not around? That kind of unpredictability doesn’t just strain relationships. It poisons them.

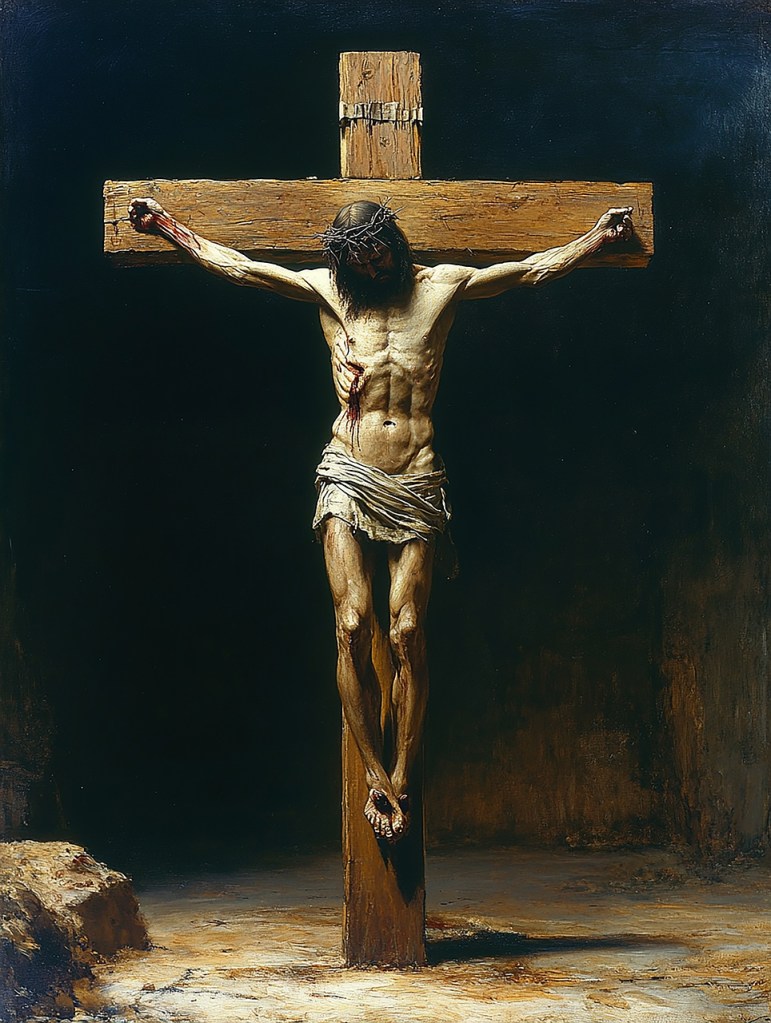

Those who know me best will attest to Thomas being my favorite apostle. I think this could be true, in part, because for all his flaws, he wasn’t duplicitous. He was as genuine as genuine gets. When Thomas questioned the Lord’s resurrection, he didn’t pretend otherwise to save face. He said plainly, “Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails… I will never believe” (John 20:25). Even better, his demand expects a non-duplicitous Savior. He expects Jesus to be exactly who He said He’d be—crucified, risen, and real—someone Thomas could touch and, once again, embrace. And when Jesus meets him in that upper room of honest inquisition, Thomas doesn’t deflect or backpedal. He doesn’t hide his unfortunate disbelief behind a persona of, “Yeah, well, I actually did know all along you were alive.” Instead, he confesses his surprise with even more excitement than his doubt. “My Lord and my God!” he cries out (John 20:28).

When I visit with other accounts that mention Thomas, I think this authenticity shines through. All along, the disciples often present personas of boldness. But in John 11, when Jesus speaks of returning to Judea, a place where He’ll almost certainly be captured and killed, the disciples express hesitation, fearing their own deaths, revealing they’re not as tough as they like to put forward. But not Thomas. He alone says, “Let us also go, that we may die with him” (v. 16). That’s not theatrical courage. It’s unbroken loyalty.

Authenticity matters. And so, I suppose in the end, that’s really what I’m aiming for—not just as a pastor, but as a man, a husband, a father, a grandfather, a friend, and a neighbor. I want to be the kind of person who doesn’t require others to guess which version of me they’re going to get. I want to be the same guy in the pulpit that I am when I’m elbow-deep in a personal struggle or riding high on joy’s sunlit upland. In other words, onlookers will know I believe what I’m preaching and teaching, and not just in public, but when no one else is around and every moment in between.

Of course, none of us can present such things with unblemished or unbroken consistency. We are all awfully imperfect. Still, by faith, believers cling to the One who is perfect—Jesus Christ—the One who is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8). Holding fast to Him, we can shed our masks. Besides, He already knows us better than we know ourselves. For me, there’s great peace in knowing this. It means I don’t need to stage my persona, but I can confess my transgressions honestly. When there’s not a minute to perform, there’s every minute to behold and follow the One who never wavers, never plays a fictitious role, and never fails to be precisely who He promised to be.