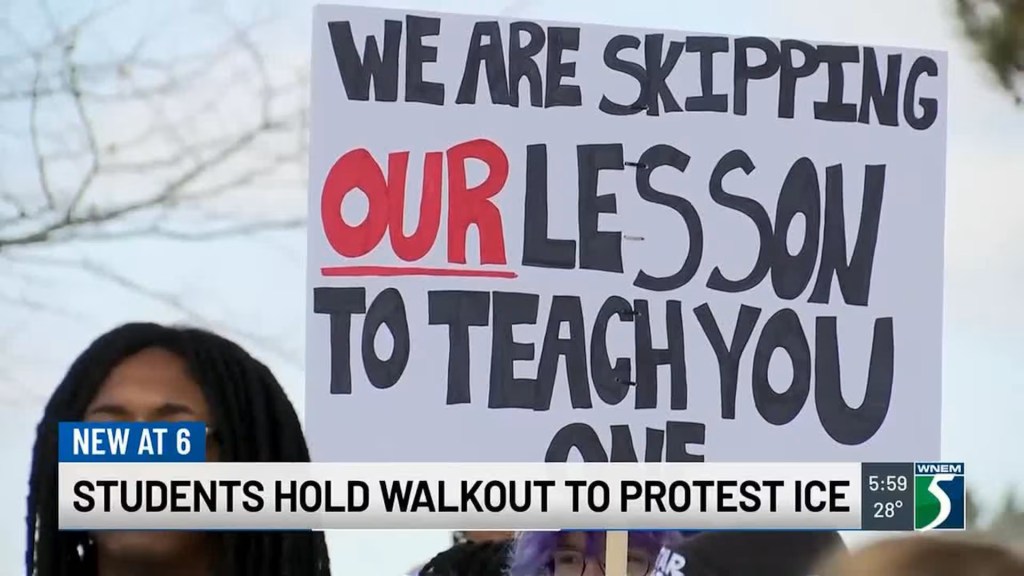

Have you seen the image circulating online that attributes a shocking confession to U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi? I have. When I saw it, I had to start searching. I wanted to know whether she really said it and, if so, what the context was.

The quotation was, “If we prosecute everyone in the Epstein files, the whole system collapses.” Again, I searched. There is absolutely no evidence that she ever said this. That matters, and it’s important to say so plainly. Things like this corrode trust, whether it comes from liberal or conservative sources.

That said, the idea embedded in the statement certainly does raise questions worth examining on their own terms. Suppose, purely hypothetically, everyone connected to wrongdoing in the Epstein files was teed up for prosecution. That most certainly would include a large number of people within powerful networks of influence. Personally, I say, get the tees and let’s get this party started. But what about the supposed system collapse? Is this spirit of concern similar to the government’s refusal to let General Motors go under back in 2008, insisting it was too big to fail, lest countless lives be destroyed? What would collapse actually look like or mean, and would it be a good or bad thing?

The point here is that the statement really does dig into a strata that’s deeper than any one person. The assumption is that it intersects with the very nature of institutions themselves. In other words, when people speak about the “system,” they rarely mean a single organization, like GM alone. They mean a web of relationships. They mean the Big Three and all the downstream suppliers. Relative to Epstein, they mean political structures, legal frameworks, media institutions, financial networks, and all the unseen relationships, good or bad, that link them all together.

In its purest sense, when acting according to its divine ordination, the “system” is in place to serve the citizenry (Romans 13:3-4). It preserves order and maintains justice. It makes sure that the courts function as they should. It ensures that laws are enforced. It keeps everyone, even the most powerful, within the same boundaries that encircle the rest of us.

But it’s pretty obvious that systems can drift. I’ve seen it firsthand, even as recently as yesterday. Over time, incentives change the nature of friendships. Goals become more valuable than truth. Narratives become more important than integrity. In some cases, the preservation of the system itself begins to take priority over the principles that justified its existence in the first place.

When that happens, the system is no longer doing what it was designed to do. It becomes less about society’s well-being and more of a self-protective, leapfrogging competition for individuals to reach the top of the food chain. In that type of system, it becomes necessary to shield wrongdoing, and the logic behind the shielding almost always becomes something like, “If we expose the wrongdoing, the damage will be too great, and the system will come undone.”

But this reasoning has hidden assumptions. In one sense, it assumes that the system, if only because it’s the best system the world has ever known, deserves to be maintained. In another sense, it assumes that if the system is allowed to continue, some wrongdoing is tolerable among those at the helm, so long as the machinery keeps running and the outward forms of stability remain intact.

I’m a huge fan of liberty, which means the first sense is immediately rejected. Indeed, the framework of our constitutional republic is the best system this world has ever seen, and it deserves to be maintained. It’s the second assumption that troubles me. It’s the one that quietly shifts the definition of justice from something principled to something negotiated. It suggests that not only are there thresholds of wrongdoing we are willing to overlook, but also categories of people who operate under softer rules, and that their preservation is somehow a higher good than truth (Deuteronomy 1:17 and James 2:1,9).

I mentioned a few weeks back that the reason my Ashes To Ashes book has resonated with so many is that, in a way, it understands the frustration among the citizenry when this becomes the accepted standard. This feeling absolutely meets with the Epstein files. Young girls were trafficked and abused by the seemingly untouchable among us. We’ve known this for years now. And still, not one person, other than Ghislaine Maxwell, has been brought to justice. There are names behind those redaction marks. Law enforcement knows who they are. But here we sit. Of course, some would say Prince Andrew was brought to justice. But it wasn’t for anything I just mentioned. He was charged with sharing government information with Epstein, even though all of it happened within the darker context of sexual deviancy with underage girls.

I’m not so sure a free society can long survive this obvious discrepancy. Liberty depends on trust that the law applies equally, that wrongdoing is answerable, and that justice is more than a slogan carved in stone above a courthouse door. The moment people begin to suspect that some are shielded while others are exposed, the real damage has already begun. The machinery may still run, the institutions may still stand, but the confidence that gives them legitimacy is starting to turn to ash. And once that foundation gives way, no system, no matter how carefully constructed, can stand for long.

As Americans, we’ve all learned the principle that justice must be impartial. If we didn’t learn it in school, then there’s a good chance we learned it in real time, or at a minimum, by watching a cop show. Either way, the point is that justice does not bend for the powerful while remaining hard and fast against the rest of us. When it does work that way, the plain truth is that justice ceases to be justice at all.

So, Pastor Thoma, what are you recommending?

Well, essentially, I guess what I’m saying is that I wonder how shining the light of truth on anything could ever be a bad idea. I don’t believe for one second that the system would collapse if all the redactions were removed. I’ve never known truth to collapse what’s good—and America’s system is just that. Instead, truth exposes what’s broken, making repair a possibility (Ephesians 5:13). That’s always a good thing. And so, my point. Whatever is broken in the system, if it’s truly worth preserving, the truth will find and make it possible to refine it, not destroy it. If parts of it cannot survive truth’s light, then perhaps those are the very parts that should not survive at all.

No matter who they are, bring the people in the Epstein files to justice. Period. America will be fine. In fact, America will be the better for it. Nothing good comes from protecting anyone from accountability. That should already make perfect sense to Christians. We know what God’s Law does. We know it’s an expression of His love (Hebrews 12:6 and Proverbs 3:11-12). He’s loving us when He says, “Don’t do that! It’s bad for you!” With God’s loving warning, the perpetrator is given the opportunity to repent and amend—to steer away from destruction’s cliff.

But what if God didn’t care enough to do this? In a practical sense, we all know that parent whose kid can do no wrong. No matter what the kid does, the parent always excuses the crime. That’s a kid who only ever gets worse. That’s a kid who’s destined to go over the cliff eventually.

I suppose societies aren’t so different. A society that excuses wrongdoing in the name of preserving itself is not preserving anything, except maybe its decay. A homeowner who kills all the cockroaches but turns a blind eye to the carpenter ants will eventually learn what that means. Decay, no matter how carefully managed, always ends in collapse.