I spent some time last night walking on the treadmill and reading. Some of what I read was from a theologian named Stephen Paulson. You may know his name. He’s an ELCA pastor and Senior Fellow at 1517. I woke up this morning still troubled by what I’d read. But it also made me concerned for you. Here’s what I mean.

There’s a book I keep within reach of my office chair. I visit it on occasion if only to refresh my memory.

The book is Literary Theory: A Brief Insight by Jonathan Culler. The book’s ultimate goal is to ask and answer questions about writing’s purpose. I appreciate the book because it deals with the dangers of writing for public consumption. It also examines a writer’s duty to prospective readers. Believe it or not, a writer cannot just scribble whatever he or she wants without at least considering some of the ways it could be reasonably received. Culler shows similar concern for the reader, insisting that the reader must know something of the writer to connect more intimately with his or her meaning. Along the way, Culler points to context as the principal conduit. He suggests that the most precise meaning for anything written arises from context, insisting that “context includes rules of language, the situation of the author and the reader, and anything else that might conceivably be relevant” (p. 91). He goes on to say that when the writer or reader enlarges context, genuine meaning comes more into focus.

Culler’s words are insightful. Indeed, context is significant. I’ve occasionally written pieces that discourage people from swimming in the ocean. I’ve shared logical reasons. But a reader will only fully realize why I do it after learning a particularly sharky story from my youth. In other words, I have a very good reason for staying on shore. The more context I provide, the more readers can align with my intended meaning. It doesn’t mean they’ll agree. But they will, at least, grasp my objective rather than impose theirs.

As a writer, the Apostle Paul is the perfect candidate for this exercise. In certain ways, Saint Paul’s context is more significant than many realize. For one, Paul went into his role equipped with human qualities few of the other apostles had. His Roman citizenship was a crucial factor. Paul testifies to his citizenship fervently (Acts 9:11, 21:39, and 22:3), recalling his birth and upbringing in the metropolitan city of Tarsus, a prominent municipality—one that Paul himself would describe in Acts 21:39 as “no obscure city.” A relatively sizeable trade location on the Mediterranean coast, Tarsus was steeped in philosophical schools, classical literature, public orations, and other such things. Life in Tarsus offered pursuits unavailable to most others in the known world. Interestingly, a stadium was built in the city’s northern part to host Olympic-style games. It’s likely that Paul, like the rest of the city’s residents, attended the stadium’s events.

Based on these contextual details, it should be no surprise that Paul often illustrates his points the way he does. He quotes poetry. He quotes philosophers. Remarkably, while Saint James speaks of the Christian life in the traditional Judaic sense—that is, as testing (δόκιμος) leading to divine approval—Saint Paul often describes it as a race, or translated literally, stadium-running (σταδίῳ τρέχοντες). The context of his upbringing sheds light on why he wrote as he did. A grasp of the context gives us readier access to his letters—his narrative style, logic, humor, quotations, apologetics, and so much more.

And since Paul is a divinely inspired writer, I can better understand what God means to say through Paul when I know the broader array of details communicating his meaning.

Relative to meaning, however, the tables are drastically turning, especially in the 21st century, where there seems to be a limitless trajectory to what words actually mean to their recipients. The devil is behind this. He lives to twist language. Language is the chosen means for communicating God’s Word. If he can make the transmission between giver and receiver unreliable, he can ultimately confuse salvation itself.

It’s no coincidence that the word gender no longer means biological sex but instead means a subjective interpretation of personal identity. Indeed, in this peculiar sense, context is boundless, as Culler mentioned. And so, writers must be careful because there’s no telling the strange filter someone will use to interpret what’s been written. Knowing this, writing becomes a more complicated task—a minefield of sorts. Doing it for public consumption requires micro-managerial care.

I don’t necessarily know if I have that skill. I certainly do try.

This brings me closer to where I began with Paulson. I mentioned a writer’s duty to readers. I would argue that duty and responsibility are nearly the same thing. Von Goethe asked, “What, then, is your duty?” He answered himself, replying, “What the day demands!” I would say that each day’s duty requires that I be responsible with the talents and treasure God has given me—that I would care for my family, work diligently in my vocation, seek faithfulness to my Lord, and the like. Because I’m a writer at heart, one who writes hundreds if not thousands of pages of content each year, I also have a duty to readers to handle language responsibly. As this meets with the remaining 99% of our world who would never consider themselves writers, this means managing information intake honestly. It means doing everything you can to understand a speaker’s or writer’s intentions relative to his words and the context birthing them. One writer many should be examining very closely these days is Stephen Paulson.

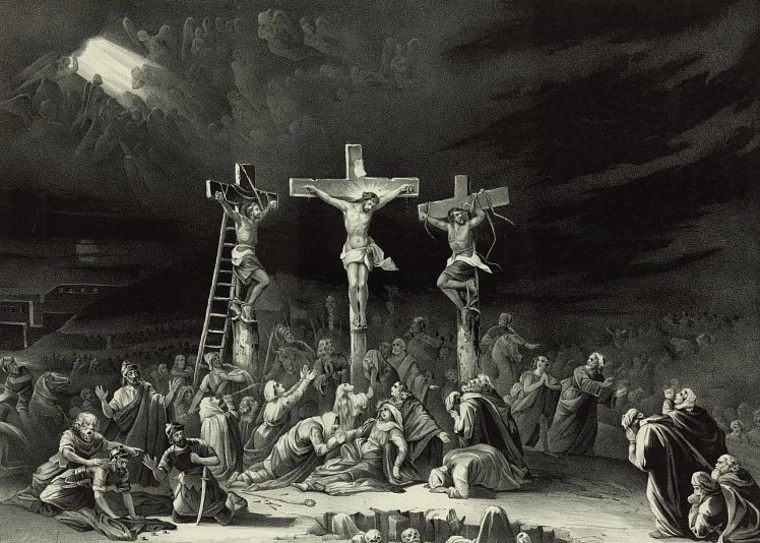

Again, Paulson is becoming popular among Lutherans in particular. He uses words that often sound sanctified. But dig deeper into the broader contexts of his words. Suddenly, they no longer mean what we assumed they meant. For example, the Bible speaks of the atonement as Christ’s substitutionary sacrifice for humanity’s sin. He had to die. It was necessary for our salvation. From there, the Bible communicates faith as the avenue for receiving the merits of this great exchange. For Paulson, he sure does go out of his way to communicate the atonement as more of a display than a necessity. It’s less about Christ fulfilling the Law’s demands or assuaging the divine wrath aimed directly at sinners and more concerned with God’s ability to show His love and say to all who believe, “You are forgiven.” With this as the baseline for the atonement, who really needs the crucifixion? Apparently, not anyone. Jesus didn’t need to die. He merely did it to show us how much he loved us.

Does the Lord’s gruesome death show us just how much He loves us? Yes. I say that in sermons all the time. But is it the atonement’s deepest purpose? No. Confusing this, Paulson can ultimately claim that God completely “disregards the Law when He forgives sins.”

But He doesn’t do that. God’s Law is never irrelevant. It cannot just be disregarded as though, by His divine omnipotence, He’s somehow capable of turning a blind eye to what is innate to His nature. God is good. His Law is good. It is fixed. And it must be kept. Either we do it, or Jesus does it and applies the benefits to us. The thing is, we’re imperfect. We can’t do it. Jesus can. And He did. He lived perfectly in our place. Even though innocent, He suffered the consequences we deserved and died beneath their incredible weight. Faith believes and receives this. By the power of the Holy Spirit at work through this Gospel, we are recreated to love His Law—to want to keep it. That’s typically referred to as the Third Use of the Law. Believe it or not, the Third Use is not apart from genuine atonement theology.

When Paulson speaks of Jesus’s atoning work, his context is different. He’s using the same word, but has an entirely different meaning. He does not mean what the Bible means. As a result, we should expect other theologies he espouses to be just as confused. How could they not? To confuse the atonement even in the slightest is to confuse the entire Gospel, making phrases like “outlaw God” and “radical grace” suspect. In fact, in his latest article, Paulson claims Moses made up the doctrine of sanctification because he couldn’t understand how God could simply declare him righteous apart from the Law. That’s a stretch and then some. However, it makes sense when I know that God’s Law is more or less irrelevant to Paulson.

I suppose I’m trying to say that a reader can thwart this confusion and avoid this nonsense when better acquainted with the writer’s contextual meanings. Of course, discerning these things takes work. But preserving truth is a laborious trade. Writer or reader, Christians are called to deal in language’s stock exchanges. When we see misdealing (the deliberate or accidental redefining of words), we call it out, enlightening others of the potentially bankrupting information swap. When we see prized opportunities communicating beautiful truths, we herald them, encouraging others to reap the same lovely benefits we did.