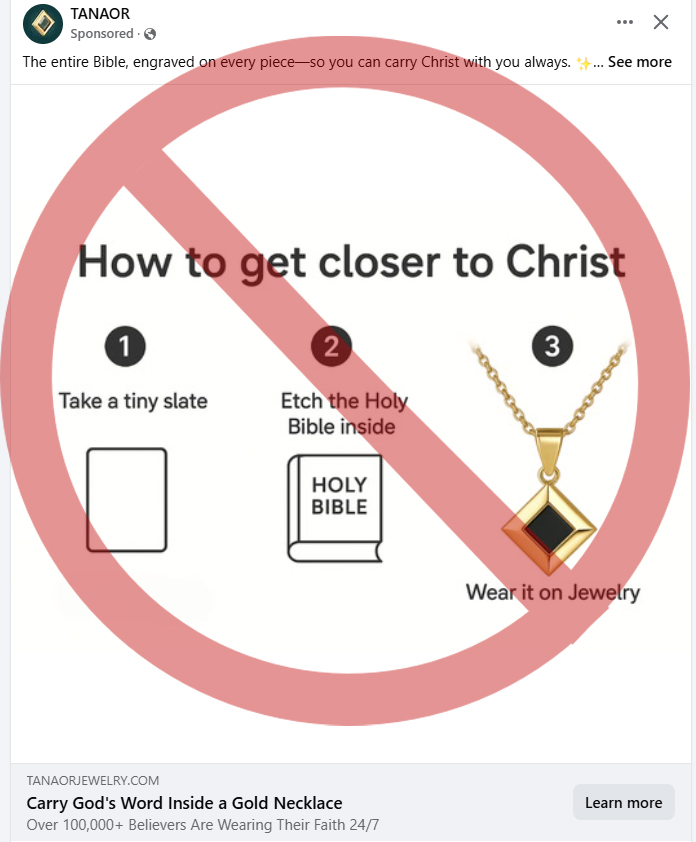

It didn’t take long for me to discover what I wanted to write about this morning. The image I’ve shared here (with the strikethrough I added, affirming my disgust) was all the inspiration I needed.

Now, before I say what’s on my mind, just know that if you purchased the item advertised, I’m not condemning you. Advertising is designed to rope us into doing things we might not normally do. However, I suppose if you succumbed to this particular advertisement, then I am concerned. With very little wiggle room for alternate interpretation, the ad implies something deeply theological, and it isn’t good.

In short, the advertisement’s premise is “How to get closer to Christ.” Next, it gives the following three steps for accomplishing this:

Take a tiny slate.

Etch the Holy Bible on it.

Wear it on jewelry.

So, plainly, a way to draw nearer to the Savior of the world—to actually be closer to Him—is to miniaturize the entirety of His written Word to a nano-size document unreadable by any human being, and then hang the document around your neck as a trinket. Therefore, by wearing the necklace, you are closer to Christ, and He is closer to you.

What’s the implied theology here? Well, before I go any further, let me first deal with what I expect will be a knee-jerk concern from readers wondering how this might be different from wearing a cross or crucifix as jewelry.

For starters, the Christian Church has long employed visible symbols—crosses, crucifixes, stained glass, icons. Lots of critics like to take aim at these things, suggesting the Church employs them as magical objects. I suppose some do. That’s unfortunate. However, genuine confessional Christianity doesn’t do this—and never did.

A crucifix, for example, places before our eyes the very heart of our faith: Christ crucified for sinners. It certainly doesn’t suggest that Jesus is somehow trapped in its wood or metal, or that the closer you are to it physically, the closer you are to Him. Instead, it visually echoes what can only be sourced from God’s Word: “We preach Christ crucified” (1 Corinthians 1:23). Even better, it demonstrates a completely different trajectory of approach, which is that “while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). This is say that while our sinful nature would have nothing to do with God, He reached to us, giving Himself in the most comprehensive way. With these things in mind, a crucifix is a devotional aid that directs the senses to faith’s genuine object, Christ, and all that His person and work entail.

The advertised pendant, however, claims to contain the Bible, yet it’s completely undecipherable. You can’t see a chapter, a verse, not even a letter. It has no visual function, no teaching capacity, no communicative power. At best, it gestures vaguely at the idea of God’s Word. But only the wearer knows that—sort of. Not even they can read it. A crucifix, by contrast, is visible. A child can look at it and ask, “Who is that?” The one wearing it now has an opportunity to share the message behind the theological cue, which is the powerful Gospel message that saves (Romans 1:16).

The trinket in question? It invites no such conversation. It says nothing and teaches nothing. More to the point, it falls flat because of why it’s being sold—which is not complicated. The company wants you to believe that by buying and wearing this necklace, you will be closer to Jesus. That’s not the same as stained glass in a church. That’s not the same as a portrait of Christ in your home. That’s not even close to the purpose of a cross or a crucifix.

The consequences of believing and acting on this advertisement aren’t small. At a minimum, the company is selling talismans—the idea that proximity to God’s Word, rather than receiving it, is sufficient for faith. That’s not Christianity. Genuine Christianity knows how closeness with God is achieved. Ultimately, He comes to us in Christ, who is the Word made flesh (John 1:14). Indeed, He comes, not micro-etched on a pendant in talismanic fashion, but through the verbal and visible means of His Word He established; where His Word is read, proclaimed, preached, and taught; in Baptism, where water and Word unite to bring forgiveness and new life; the Lord’s Supper, where bread and wine are His body and blood, given for you.

Conversely, this pendant nonsense is little more than a devotional gimmick being sold in the marketplace of false teaching. It’s the kind of shallow spirituality that resulted in Jesus turning over tables (Matthew 21:12-13) and rebuking church leaders (Matthew 23:25-27).

I sometimes wonder how things like this gain traction. I suppose it’s because the ad uses Christian-like language and images, which makes it sound harmless, maybe even holy. But the message is upside down. Unfortunately, that’s entirely possible in a culture and world brimming with churches plagued by Christian illiteracy. This ad didn’t appear in a vacuum. It thrives in places where spiritual depth is replaced by shallow sentimentality. That someone thought this ad would work (and probably has metrics saying it does) is a sad commentary on what people think Christianity is. It also testifies to a generation raised on inspirational memes instead of catechesis. It signals a Christian faith that’s been gutted—hollowed out by unchecked religiosity peddling subjective emotion over objective doctrine.

Again, if you bought the pendant because you thought that by doing so you’d be closer to Jesus, I’m sorry. I’m not sorry if my words have offended you. I’m sorry that you didn’t know any better. I’m sorry that somewhere along the line, someone convinced you—or failed to love you enough—to correct the faulty notion that closeness to Christ could be achieved through anything other than the means He Himself instituted. I feel terrible that marketing has become so indistinguishable from ministry in our culture that it’s hard to tell the difference between a product pitch and a proclamation of truth, resulting in people spending their money on something that will not get them where they want to go.

But even as I’m sad about these things, I’m also hopeful. Because now you know that Jesus is not found in a pendant, no matter how cleverly it’s designed. He’s found where He promised to locate Himself: His verbal and visible Word, the Means of Grace. These means aren’t slick. If anything, they’re so mundane they’re unmarketable. Still, they are eternally powerful. And they’re yours, not by purchasing power, but because the God you could never with all your mortal intellect and strength draw near to loved you enough to draw near to you.