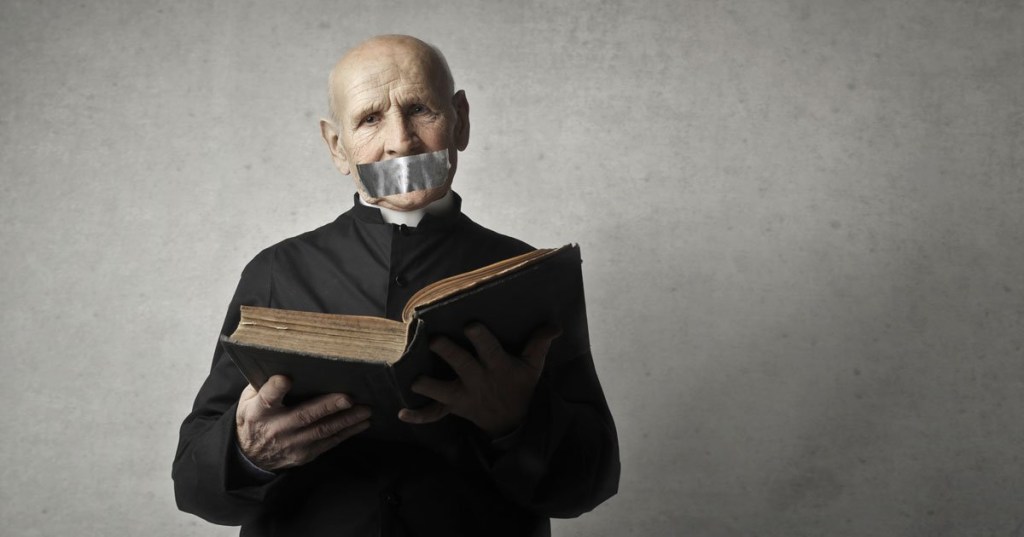

The introduction in the current draft of my sermon for this morning includes a warning. I offer the warning because, sometimes, the deepest intention of a particular portion of God’s Word isn’t so gentle with its recipients. Sometimes, it’s razor-sharp, cutting us in ways we’d prefer it wouldn’t.

This morning’s Gospel reading appointed for the Last Sunday in the Church Year—the parable of the Ten Virgins in Matthew 25:1-13—is one such text. It steers into and ends with some words that Jesus has warned in other texts He’ll inevitably use on the Last Day. To have them directed at oneself would be to experience terror above all terrors. Time will have run out. All bets will be off the table. The divine lights of God’s standards will beam with unmatchable brightness, incinerating all disbelief or untruth. Nothing will be hidden. Those who are prepared will be welcomed into eternal glory. With chilling brevity, He will look to others—the unprepared—and say, “I do not know you.”

This whole scenario carries in its pocket a particularly crucial assumption. As the Creeds have long maintained, when Jesus returns, He will do so as the divine Judge, saying yes to some and no to others during eternity’s first few moments.

For some, this is an uneasy image. Why? Because it opposes everything human sinfulness prefers of its gods. It meets a certain kind of Christian, too. The Jesus embraced by some in American Christianity is mushy, being more than willing to let us shape Him to fit our preferences. He doesn’t get annoyed when we twist His Word. He’s not the least bit uneasy when we muddy His natural law. He isn’t so bothered when we skip worship Sunday after Sunday, arguing that we can be His people on our own time and our own terms. He’s certainly not going to be so arrogant as to tell us we’re wrong—that we’re headed for destruction. The Jesus some prefer could never bring wrath, only hugs. He doesn’t decide what’s good or bad. He lets us decide. And then, no matter what we choose, He smiles with satisfaction that we’ve done what makes us happy and pursued personal fulfillment.

The Gospel reading for this morning would say, if this is your Jesus, you’re done for. Or, more akin to the parable’s intention, you’re unprepared to meet the real Jesus on the Last Day.

I’ll say that today. It’ll be tough to hear, even for me. Why? Because I’m no different than the folks in the pews. I’m so often a self-interested sinner.

We’re all in this together.

Something I won’t specifically say in the sermon but will share with you here is that Jesus often measured His hardest words against hypocrites, which is probably why only a few paragraphs after this parable, the reader discovers, “Then the chief priests and the elders of the people gathered in the palace of the high priest, whose name was Caiaphas, and plotted together in order to arrest Jesus by stealth and kill him” (Matthew 26:3-4). Jesus regularly pointed to these men as being those who, and they knew it. This parable about preparedness certainly has hypocrisy in mind.

Preparedness is impotent without self-reflection. The whole point of readiness is genuine self-honesty. It asks, “What do I know is true about my situation and condition? What, where, and how will I acquire what I need to be prepared?” It’s not far from Jesus’s point that Christian endurance will be one of self-reflection resulting in repentance and faith. Christians will know by faith to confess, be absolved, and recalibrate—to continually refill and trim our lamps.

On the other hand, hypocrisy is the absolute manifestation of self-deceit. It lives a dangerously duplicitous existence, believing it has enough of what it needs in itself. It believes one thing, most often for self-exemption, while being something altogether different.

Examples of hypocrisy are all around us. We all do it. A perhaps minor, yet still relevant, example that comes to mind concerns a photo I posted on Facebook of our family’s nativity scene. One or more kids and I will add various action-figure characters from around our home to the display each year. We’ll put Star Wars characters, aliens, you name it, all standing at attention before the Christ-child cradled in Mary’s kindly arms. We do this mindful of Christ’s return at the Last Day, paying closest attention to Saint Paul’s Advent nod to the Lord’s return in Philippians 2:5-11:

“Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. Therefore, God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.”

Paul just told us that Jesus, the Son of God, crossed from the divine sphere to ours in absolute humility, His trajectory being that of the cross. A nativity scene teaches these things. Christ arrived in lowliness, emerging from the Theotokos among animals that feed from a manger. Advent—a time when someone might set up a nativity scene—makes visual the message’s connective tissue. Traditional churches celebrating Advent will know the season’s historic purpose is to rejoice in the Lord’s first coming while penitently anticipating His return. It’s no wonder that, after noting the incarnation and death, Paul moves straightway to the events of Last Day. Our nativity scene has these things in mind. It knows the incarnation. By its traditional characters, it knows the Gospel texts that make clear His purpose (Luke 1:26-38, 2:8-18; Matthew 1:18-25, 2:1-12; John 1:1-14). By the stranger figures we add (which, when choosing them, admittedly, sprinkles in some humor), it understands Paul’s conclusion, which is that everything—visible or invisible, angel or demon, believer or unbeliever, all human fictionalities and all absolute truths, all things in heaven and on earth and under the earth—will bend in submission to the crucified and risen Christ at the Last Day. Prepared or unprepared, all will call Him Lord.

Again, I posted a picture of our nativity scene on Facebook. I even added the relevant text from Saint Paul’s letter to the Philippians. Shortly thereafter, a fellow pastor who enjoys trolling me added a sarcastic comment (which I deleted) implying that by putting fictional characters into the scene, I was making unholy that which is holy, and thereby insinuating Jesus Himself was fictional.

That’s a stretch, even for some of my worst critics.

My point here: It was a hypocritical response on his part, especially since he’s no stranger to enjoying Babylon Bee memes portraying Jesus saying things He didn’t say. By the way, I see those articles and laugh, too. Why? Firstly, because I have a sense of humor. Secondly, what I see, while out of the ordinary on the surface, has a far deeper meaning, pointing to something truthful. That’s how satire works. However, since the Babylon Bee’s fictional words are attached to Jesus as a direct quotation, sometimes even in a way that might be offensive to some, is the image making unholy and mythical that which is holy and true? No. But again, you need to be capable of genuine self-reflection that can see one’s beliefs and actions rightly. Devout hypocrisy cannot do this. It holds blindly to its own agenda, unable to see anything else, often resulting in an equally devout hatred for others—just like the Chief Priest and elders in Matthew 26:3-4.

At the end of the parable, Jesus says, “Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour” (Matthew 25:13). The Greek word used for “watch” is γρηγορεῖτε. It’s an imperative verb. It means to stay awake. But it doesn’t just mean to wake up and pay attention. It means to remain alert, ever ready, and on one’s tiptoes, looking to the horizon. Jesus chose this word because His aim is vigilant preparedness.

At its center, preparedness means faith in Jesus. But Jesus’s parable included many more details than the flickering flame of faith. He also spoke of a mindfulness that acts. This action starts with self-reflection. The wise virgins began and stayed there. The foolish virgins didn’t.

Again, and indeed, the Lord makes clear that faith in Christ saves. The arriving bridegroom identifies the wedding party by its lighted lamps, and they are the ones ushered into the wedding feast. But don’t forget the rest of the parable’s details. Don’t lie to yourself. Admit to your tendency to believe one way but live another. Then, go to church. Fill your lamps with the oil of God’s merciful love through Word and Sacrament—the preaching and administration of the Gospel in its verbal and visible means. You’ll hear the Lord’s instruction to be ready and be immersed in the bountiful gifts that make it so.