I want to begin this first Sunday in the new year by telling you a story that, on its surface, might seem somewhat trivial. It’s the tale of an awkward social exchange. I only share it because, first, it’s a new year, and second, after spending a month or so simmering with it, I realize that what happened reveals something far more serious about the spirit of our age than I first imagined—and the realization is ripe for New Year’s resolutions.

About a month and a half ago, Jennifer and I attended a small local event together. As we walked into the room, I noticed two former members of Our Savior already seated a few rows from where we’d entered. For clarity, they’re not “former” because of a personal conflict with another member in the church, or because I offended them by skipping over them at the communion rail by mistake. They left because they were offended by the kind of message you’re reading right now—the same kind I’ve been writing and sharing every Sunday since 2014. Within each, my cultural and theological conservatism, along with the moral convictions it produces, is laid bare without apology. Some people appreciate the messages. Some don’t.

As I said already, it was a small event. Therefore, the space was relatively empty, leaving no ambiguity about what followed. We saw one another clearly. I waved, smiled, and said hello. They turned away. Attempting ordinary human decency, I called out a brief question, nothing cumbersome, just the sort of small talk people use to acknowledge one another’s presence. One did respond with a relatively disinterested gesture, but he did so without looking at me. That was all. No eye contact. No further acknowledgment of my presence as a fellow human being.

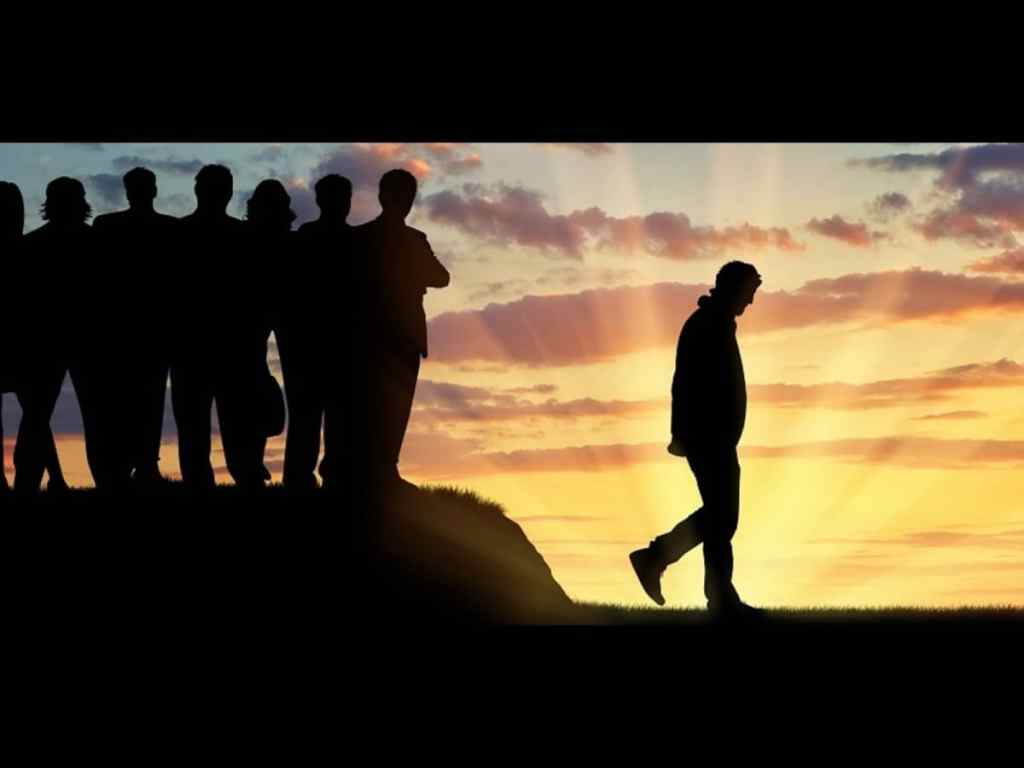

The very next week, the same scenario repeated itself, almost theatrically so. This time, I was alone. I entered the room through the same door. The same couple came in immediately behind me. I greeted them again. This time, there wasn’t even an awkward acknowledgment. They simply ignored me. Moments later, as a handful of couples filed in and found seats beside them, I watched and listened as they warmly greeted others—smiling and calling out hellos to people by name—leaving me to feel the sting of their dismissal and the sense that, for them, I did not even exist.

Now, before we rush to psychologize motives or nurse grievances, let me at least explain that what follows is not about wounded pride. I already know I’m despised by plenty. It goes with the pastoral territory. And unfortunately, I’m used to it. That means I can do what I do without coming undone when someone fails to be polite. Funny thing—Jennifer and I just went out to lunch together last week and we talked a little about the flak I catch for things I write and share publicly. She is perpetually amazed that I continue to subject myself to the inevitable scorn. From my perspective, as a Christian, I am called to endure far worse than social coldness. I mean, what I experience is nothing like what’s happening to Christians in Nigeria on a daily basis. Countless are being killed for their confession of Christ. And so, it’s easy enough for me to write and share a personal observation or cultural critique—and maybe why they matter, especially among Christians.

This morning, I’m examining something I’m pretty sure most folks have experienced. Essentially, it was the cold and corrosive behavior of shunning.

I suppose, in a clinical sense, shunning means treating someone as if they are unworthy of basic acknowledgment, not necessarily because they have done harm, but because they believe differently from you. It’s a way of saying, “You’re beyond the borders of my tribe, and therefore, are not owed my kindness.”

I dare say that, in our current cultural moment, shunning has become a favored tool for pretty much everyone. I catch myself doing it on occasion, too. For the most part, I think many do it to avoid confrontation. I get why that might happen. And maybe that was true in this case. Although my kindly greetings on both occasions should have implied friendliness rather than contention, which suggests another way people wield it. They shun, not to avoid confrontation, not to correct wrongdoing or pursue truth, but to punish dissent and signal some sort of superiority in the relationship. And, of course, it conveniently shields them from the burden of actual engagement, which could lead to reconciliation and peace. If you have no interest in these, then shunning is essential.

Knowing these things, here’s where genuine Christian analysis should probably step in.

I’d say the first step in the analysis is to deal with our excuses. In other words, I know there will be some who immediately jump to texts like Ephesians 5:11-14. Saint Paul tells the Church not to “participate in the unfruitful works of darkness,” but instead to “expose them” (Ephesians 5:11-14). Perhaps assuming the reader already knows that Jesus called His people “light” in this dark world (Matthew 5:14), Paul goes on to say that darkness is exposed by light (v. 13). With this in our theological pockets, Paul’s point is not complicated. He doesn’t want God’s people associating (συγκοινωνεῖτε—binding to something) with sin in ways that condone or accommodate it. In other words, a Christian would not want to attend a gay relative’s wedding lest they be considered supportive of such things.

Now, for those who remain desperate to write off someone with whom they disagree, try to notice what Paul did not say. He did not say to act as though anyone with whom a Christian disagrees does not exist. He did not say to write that relative out of your life completely. Instead, he told the Christians to do what light does. It shines in the darkness. Darkness cannot be overcome by a light that withdraws to another room. If light is going to disperse darkness, it must be present to do what light does.

And so, I suppose the second step in the analysis is to admit the extremes of this truth, which is that God’s Word is unambiguous about how we are to treat those who despise or oppose us. Jesus commands us to love our enemies, bless those who curse us, and pray for those who persecute us (Matthew 5:44). Saint Paul exhorts believers to live peaceably with all, so far as it depends on you (Romans 12:18). Even when church discipline is required—which is a rare and serious matter—it’s never enacted through petty contempt or silent scorn. It’s done openly, soberly, and with the goal of reconciliation and restoration (Matthew 18:15-17, Galatians 6:1, and 2 Thessalonians 3:14-15).

What I encountered was none of that. What I encountered was a posture that says, “Your very presence is a problem for me, and as such, your worth is negotiable.” That posture does not come from Christ. It stirs in sin’s darkness. Tragically, many Christians absorb this posture without realizing how thoroughly it contradicts the faith they profess.

I guess what I’m saying is that the Church and her Christians should know better. The Christian faith does not permit us to reduce people in this way. Certainly, at a minimum, it absolutely does not excuse discourtesy, let alone allow it to be demonstrated publicly so that it teaches the watching world something about Christianity. And what’s being taught exactly? That Christians believe some people are not worth basic human kindness.

But Christians do not believe that. The ones who do should check themselves carefully.

As usual, I’ve made New Year’s resolutions. I know some folks dog the idea. Well, whatever. I prefer to be more contemplative and deliberate with my life. Having just passed through 2026’s front door a few days ago, I find myself returning to moments like these, not with bitterness, but with resolve. Observing these things through the lens of the Gospel, as I prefer to do, they nudge me toward a more focused faithfulness. If the culture is growing colder, then I want to grow warmer. If silence is being used to wound, then I want my words and gestures to heal. Again, darkness is scattered by light, and Christians are children of that light (1 Thessalonians 5:5 and Ephesians 5:8).

Relative to the moments I shared with you, what does all of this mean specifically? Well, it means I am resolved to offer a friendly wave toward someone who’d much rather back over me with his or her car. I will continue to smile. I will continue to say hello. Not because it is easy. Not even because the kindness will be returned. But because Christians are not called to mirror the culture’s contempt. We are called to resist it. And sometimes, that resistance looks as small as refusing to pretend another human being doesn’t exist.

Now, for those who may be looking at me right now in their rearview mirror while revving their engines, know that even as my enemy, you mean something to me. And if there’s a chance we could be friends, I’m game to make it possible. Again, that’s one of my resolutions for the new year. I promise I’m going to be more deliberate in the effort.