I’m so incredibly exhausted by the world’s news cycles. Each new day brings a brand new insanity. So, here’s the thing. How about we just swim around in our own weirdness as Christians for a moment? Here’s what I mean.

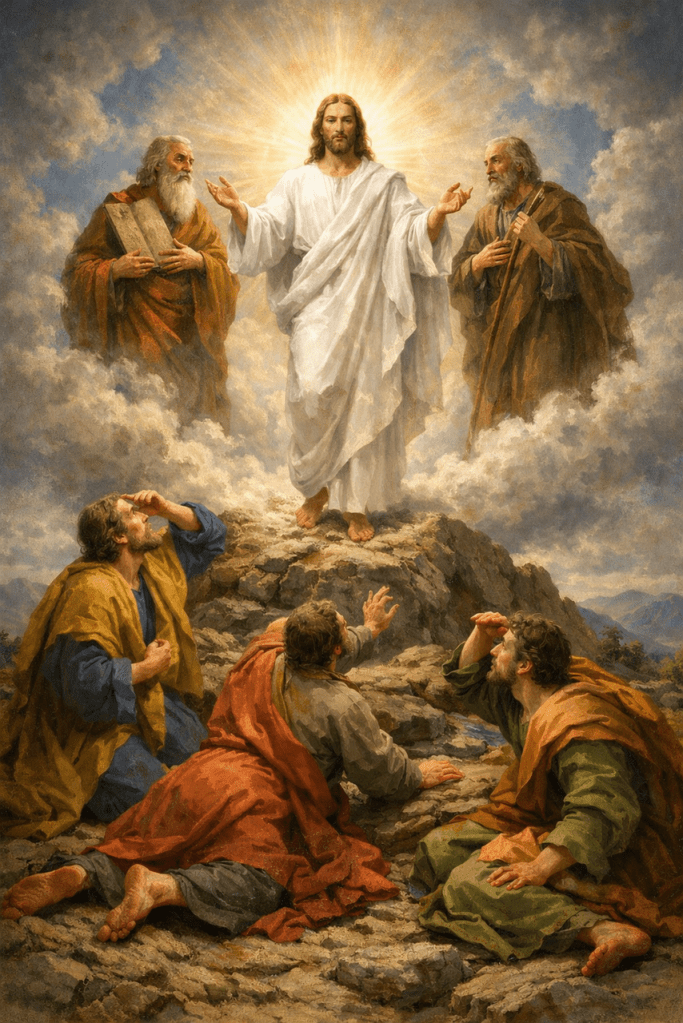

For starters, I’m only late to this topic for those who follow the historic lectionary, which we do here at Our Savior. For everyone else in the liturgical community, the Transfiguration of Our Lord will likely be celebrated this Sunday. The next stop—Ash Wednesday.

I suppose another reason I say I’m late to this discussion is that after worship here at Our Savior three weeks ago, during the Adult Bible Study hour, I shared a thought I had while preaching on the text for Transfiguration Sunday from Matthew 17:1-9. Yes, it landed on me in the middle of the sermon. It didn’t make it into the sermon. But it certainly was rattling around in my brain. Essentially, I wondered whether it might be plausible that Moses and Elijah, the two patriarchs who stood and spoke with Jesus on the mountain, were actually stepping into that moment from moments in their own time.

I shared that thought with the adults in the Bible study. However, I never finished the thought. And so, this is it.

Typically, the moment Moses and Elijah arrive is interpreted as a visit from heaven. But the whole thing seems almost too dense for that simple deduction. I mean, if this is merely a visit from heaven, even just to serve as witnesses, why does the moment feel so heavy with the entire history of divine revelation? I know it’s not a good idea to form theological positions from speculation. However, I guess what I’m wondering about is not merely what happened, but how deep the event actually runs into the fabric of the Old Testament accounts. When Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus on the mountain, is something more taking place? Is time and space converging? Is it possible that when Moses and Elijah encountered God in the Old Testament, they were, in one or more of those moments, actually meeting with Christ in the Transfiguration moment? Is this something that—not merely theologically, but actually—is a binding moment that shows the simultaneous reaching backward and forward of redemptive history? Christianity teaches that such things are true. But is it being demonstrated in the Transfiguration?

I know it might sound like a huge waste of time to some. Still, the New Testament provides the necessary theological foundation for at least asking the question. Saint John writes pretty plainly, “No one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known” (John 1:18). Christ Himself says, “Not that anyone has seen the Father except he who is from God” (John 6:46). And yet, the Old Testament repeatedly describes Moses, Elijah, and others as truly encountering God—speaking with Him, seeing His glory, standing in His presence. What’s more, the Church has historically resolved this tension by confessing that all visible manifestations of God in the Old Testament are manifestations of the pre-incarnate Son. In other words, whenever God shows Himself to anyone, Christ is the One they see. One of my favorite professors, Rev. Dr. Charles Gieschen, has written a crisp resource that leans into this kind of stuff. His book Angelomorphic Christology: Antecedents & Early Evidence, while thickly academic, is great fun.

In the meantime, these things place Moses’ experience on Sinai in an entirely new light—no pun intended. Exodus 33:11 tells us that “the Lord used to speak to Moses face to face, as a man speaks to his friend,” and yet moments later, Moses is told that no one can see God’s face and live. The paradox only resolves if the One Moses encountered was truly divine, yet not the invisible Father in His fullness.

Something similar happens with Elijah’s encounter at Horeb. The prophet stands on the mountain as the Lord moves by, accompanied by wind, earthquake, and fire, yet is finally revealed as God speaking to Him in a quiet voice (1 Kings 19). The text uses the same language of divine self-disclosure found in Moses’ encounter—“the Lord passed by”—and, like Moses, Elijah returns from the mountain back into historical time, commissioned once again for his prophetic task of preaching a faithful Word. Like the scene with Moses, though happening at different times, this one includes the mountain, the divine glory, the overshadowing presence. Once again, the Transfiguration account begs the same question—if no one has seen the Father, who was Elijah encountering?

I don’t want to force anything into this. Eisegesis is dangerous. Still, the Transfiguration itself seems almost designed to invite a deeper investigation.

Another quick thing… Saint Luke’s version of the Transfiguration account tells us that Moses and Elijah speak with Jesus about His ἔξοδον—literally, His “exodus”—which He is about to accomplish at Jerusalem (Luke 9:31). First of all, the disciples weren’t invited into this discussion. He was talking to Moses and Elijah. Second, this isn’t casual vocabulary that Luke used. Moses’ entire ministry is defined by the Exodus. And Elijah stands at the head of the prophetic tradition that would proclaim what the Exodus was all about—calling Israel back to the covenant, confronting false worship, and insisting that the God who delivered His people is the same God who remains faithful to the end. And both Moses and Elijah are, right now, on the mountain with Jesus, talking about the fulfillment of everything they were commissioned to enact or proclaim.

Well, okay, one more quick thing. Did Jesus wink toward the possibility of the kind of collapse of linear time that I’m talking about when He said to the Pharisees in John 8:56, “Abraham rejoiced that he would see my day. He saw it and was glad.” Not merely believed it, but that he saw it. I think Hebrews echoes this too when it says that the faithful of old did not receive the promise apart from us, because their perfection awaited Christ (Hebrews 11:39-40). Their story was never complete in their own time. It awaited His appearing.

In the end, is any of this provable in a strict sense? Nope. Not at all. Scripture never explicitly states that Moses was temporally present at the Transfiguration while also standing temporally on Sinai, or that Elijah consciously stepped into a future moment with Christ while at Horeb. But as I said, I thought about this right in the middle of my sermon on the Transfiguration, and this morning I decided to have a little fun with it, especially since I left it hanging during Bible study a few weeks ago.

I suppose, through all of this, regardless of the theological wandering, we did land on something the Bible establishes pretty firmly. It’s something that the dispensationalists may want to keep in mind. Essentially, all divine self-revelation is Christological, all theophany is mediated by the Son, and all redemptive moments converge in Him. Time in Scripture is not merely sequential. It’s centered—situated entirely in Jesus. You cannot be God’s people apart from Christ, who was, is, and will always be.

So, before the private messages start arriving, calling me crazy or saying I have too much time on my hands (which I absolutely don’t), I suppose the safest and most faithful way to close up shop on this is not in terms of literal time travel, but in terms of unveiled continuity. When Moses and Elijah encountered God in the Old Testament, they encountered Christ, though they did not yet know Him as Jesus of Nazareth. In other words, while Moses and Elijah were there at the Transfiguration, no matter where they came from, they weren’t visiting with someone or something new. They were visiting with the same One they’d been with during their own theophanies in their own time.

In that sense, even the Transfiguration becomes less about Moses and Elijah showing up, as if they’re appearing to the disciples alongside Jesus, and more about Jesus appearing as He is to and with Moses, Elijah, Peter, James, and John—with an element of enlisting the new guys into the same company that has always stood before Him, now finally seeing Him without the veil.

And so, however you feel about what I’ve written this morning, rest assured, it was a far better way to spend my morning than simmering in everything else going on in the world. Although the student walkouts deserve some consideration. Maybe I’ll be “unexhausted” enough to think about those things for my regular eNews message this Sunday.