You should have figured I’d sit down to write something to you this morning. How could I not? You’re family, and if there’s anything that families almost certainly do together at Christmas, it’s sit and remember, finding joy in familiar things and the memories they stir. Indeed, familiar things are often comforting things. We know them well. We know their sounds and scents. We know how they feel in our hands. And when we interact with them, we are strangely at ease. Christmas has a way of introducing and reintroducing this sensation every year. It did so for me last week. Let me tell you how, and in the best way I know how—by telling you a story.

My Grandma Thoma had a small candy bin on a side table near her couch that she kept filled with the chalky pink mints you might find at a bank or funeral home. Of course, as kids, we didn’t care. Candy was candy. Anyway, the round bin, about as big as a coffee mug, was by no means an extravagant vessel. Rough and unpainted, its old metal was worn. Its hinged top was challenging to open. Even worse, it screeched like a haunted mansion’s front door, assuring that any would-be candy thieves were swiftly apprehended. Still, whenever the grandchildren came for a visit, we were allowed to pass it between us, each taking a piece of its contents for ourselves.

One year at Christmas, having received the required wink of approval from Grandma, my brother and I opened the bin and found striped peppermints instead of the usual chalky pastels. We smiled. She smiled. I still remember that relatively insignificant Christmas moment.

I haven’t seen the candy bin in decades. I don’t know what happened to it after she died. My guess is that someone in the family—an aunt, uncle, or cousin—took it home and has it sitting somewhere on a shelf. At least, I hope it is. Either way, why am I telling you this? Because for some strange reason, this Christmas memory of my Grandma and her candy bin returned during last week’s Children’s Christmas service here at Our Savior. The recollection started just as the children began singing the familiar Christmas hymn “The Angel Gabriel from Heaven Came.”

Somehow, the hymn’s beautiful familiarity triggered the equally familiar scene with my Grandma. It’s as if the image swept in with Gabriel’s grand entrance in stanza one, his “wings as drifted snow, with eyes as flame.” There, on the lectern side of the chancel, somewhat hidden behind our congregation’s glistening Christmas tree, the setting itself conjured an intersection of comfort, familiarity, and ease—a thread of reminiscence resonating through the sacred spaces and carried on the voices of children.

But that’s not all. Throughout the rest of the midweek service’s “Lessons and Carols” portion, more memories arrived. I started thinking about the snow forts my brother and I built in our side yard near the neighboring tavern. Then, suddenly, I was transported to the hospital room the day my brother died. But I didn’t stay there for long. My thoughts turned to something else.

I recalled hooking my childhood dog, an Alaskan Malamute named “Pandy,” to a sled to pull my little sister, Shelley, around the yard. I remembered Pandy wasn’t too interested. I thought of summer days on my bike, cruising the neighborhood with friends. I remember jumping a ramp we set up. It did not end well. I crashed and was pretty skinned up. But still, there was more.

I could see as clearly as if it were yesterday, a wintry evening with my son, Joshua. We built a snowman that managed to remain upright and smiling for several weeks. I also remember how concerned I was as we struggled to keep our house warm.

Flickering like candles in my mind, I recalled summertime basketball with the kids in the driveway. I remembered lifting Madeline from the ground to get her as close to the rim as possible so she could finally make a basket. I remembered doing this while Harrison and Evelyn tooled through and around on tricycles or scooters. I recalled how concerned I was when Harrison ended up in the hospital with a staph infection that nearly took his life and how Jennifer and I essentially lived in the hospital with him until, after several surgeries, he could finally go home. I remembered the same when Evelyn was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. I remembered sitting with Jennifer on our front porch, admiring the hostas she worked so hard to cultivate. I recalled coming out the following day to discover that the deer had eaten all of them.

In all, I thought of good times and harder times, joy-filled and terrifying.

Now, someone might be tempted to say, “It sure sounds like your mind was wandering during the carols and hymns. Shouldn’t you have been listening to the words? Shouldn’t you have been thinking of Jesus?”

I was listening to the words. In fact, anyone watching would’ve seen I was singing along. And I was definitely thinking of Jesus. More importantly, I was thinking of how He is forever thinking of me. Immersed in the Christmas hymnody’s glorious familiarity, more than once that night, it was so easy to whisper things like, “Thank you, Lord. You’ve been so good to me.”

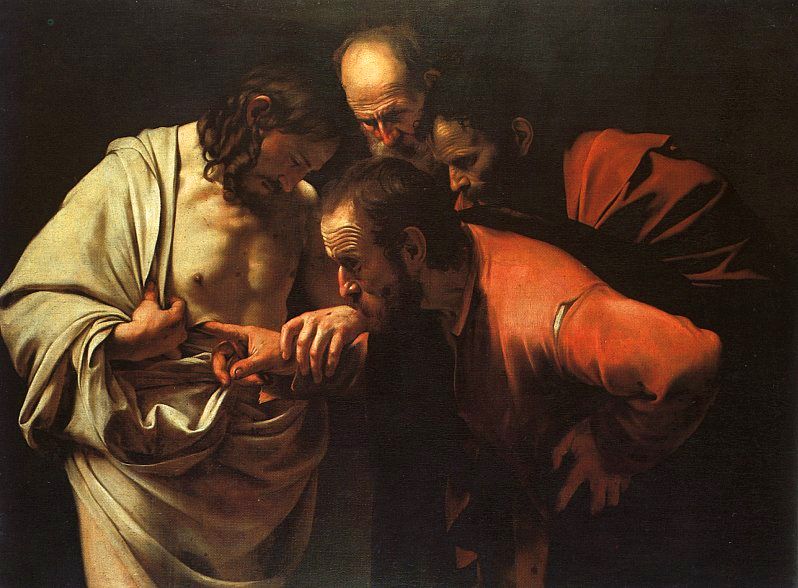

Still, what would prompt the memories and whispers? Well, singing “What Child Is This” certainly played a part. If done right, it’s a moving hymn. I preached as much at last night’s Christmas Eve service, reminding the listeners of that particular moment in the lullaby that requires us to confront the reason for the divine Child’s birth. We sing, “Nails, spear shall pierce Him through, the cross be borne for me, for you.”

There were other moments wafting on the children’s glad Christmas sounds with the same potency. In “Of the Father’s Love Begotten,” when the congregation joined the children to exclaim, “Pow’rs, dominions, bow before Him, and extol our God and King. Let no tongue on earth be silent, every voice in concert ring, evermore and evermore!” Even better, the hymn’s final Trinitarian verse! Listen for yourself to the recording: https://www.oursaviorhartland.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/REC12-18-24.wav. It’s not the best audio capture. But still, did the angels suddenly decide to join us? Was the recorder clipping at the end, or was that divine applause?

I don’t know about anyone else, but those moments pulled me like a tractor beam into times that mattered—both good and bad—all wrapped in God’s unmistakable grace. My thoughts weren’t wandering. They were enslaved by the thrilling joy of Christ’s incarnation—Immanuel, God with us!—and what that means for my past, present, and future.

So, where am I going with all of this? Well, as always, I’m thinking it through on my keyboard.

Looking back at what I’ve written so far, I suppose there’s a basic nature to what I’ve described. In other words, familiar things have a way of anchoring us—an innate way of reminding us who we are and where we’ve been. A Christmas hymn sung by children reminded me of being a child and visiting my Grandma at Christmas. Along with it came an object any child would remember: a candy bin. But as the hymns continued, more moments came into view. Admittedly, Christmas is already second to none when it comes to sentimentality’s sense and the basic nature I described. And yet, for Christians, there’s still more to this.

As the secular world is moved by pristinely wrapped presents, evergreen and cinnamon smells, and Frosty the Snowman, I suppose I’m also saying that for Christians experiencing the same sentimentality, we can actually reach Christmas’s truest destination. We know its purpose: the incarnation of God’s Son to rescue us from Sin, Death, and hell. With that in sentimentality’s hand, we can grasp at the fragments of our lives, assured that the moments of joy, sorrow, struggle, and triumph form a tapestry of God’s grace. They’re not bygone moments. They all bear reminders that God, in His infinite love, came into our world not only to save us but to walk with us through every season of life—that all along the way, and still to this day, Jesus is thinking of us.

I guess I’ll just leave it at that. I need to start preparing for this morning’s service.

That said, may today’s Christmas celebration and all its comforting familiarities be more for you than holiday jingles and opening presents. May the festival of Christ’s birth be an anchor fixed to God’s wonderful promises. Indeed, unto us, a child is born! Unto us, a son is given! It’s Jesus! O come let us adore Him, Christ the Lord! Merry Christmas to you and yours!

It’s very early, 5:30am to be precise. I’m writing this note from Cantrall, Illinois. Again, to be precise, I’m at Camp CILCA, which is just outside of Springfield.

It’s very early, 5:30am to be precise. I’m writing this note from Cantrall, Illinois. Again, to be precise, I’m at Camp CILCA, which is just outside of Springfield. The season of Lent is a powerful time in the Church Year. Throughout its forty days, if there’s one thing in particular it draws out and defines with its penitential crispness, it’s the authenticity of human guilt.

The season of Lent is a powerful time in the Church Year. Throughout its forty days, if there’s one thing in particular it draws out and defines with its penitential crispness, it’s the authenticity of human guilt. Just yesterday (Saturday, February 20), the Life Team of Our Savior blessed our church and community by offering an “End of Life” seminar. It was well attended. I was glad for that.

Just yesterday (Saturday, February 20), the Life Team of Our Savior blessed our church and community by offering an “End of Life” seminar. It was well attended. I was glad for that. The penitential season of Lent is soon to be upon us. It begins this week with Ash Wednesday.

The penitential season of Lent is soon to be upon us. It begins this week with Ash Wednesday.