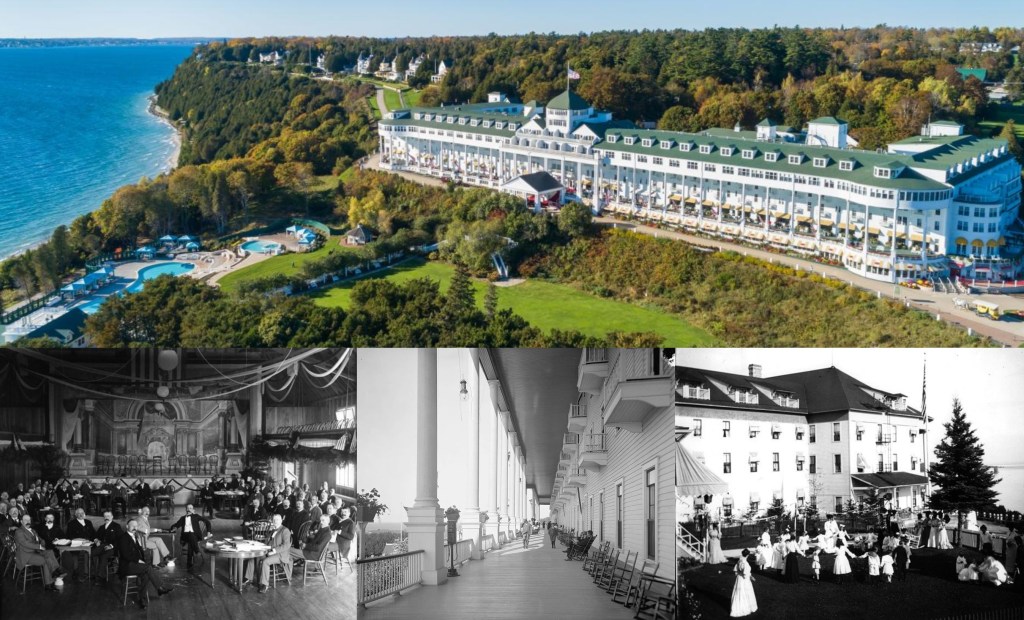

I’m writing this note from the lobby of the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island. I was one of the invited speakers at the Michigan Republican Party’s leadership conference. In truth, I almost didn’t feel like writing this, mainly because when I crept from my room at 5:00 a.m., not only did I discover I was the only guest awake in the whole place (as you can see from the photo), but the landscape was entirely void of coffee. If there’s one thing I require before typing this early morning note, it’s coffee.

Now, for a relative story before moving on to something else.

Carlos, a man traveling through and cleaning the lobby light fixtures, greeted me warmly. I asked if he knew where I might find a cup of the elusive brew. His apologetic answer: None would be available until 6:30. Downcast, I situated myself in a chair to begin typing. However, barely a moment passed before Carlos, having just climbed a ladder to start cleaning a chandelier, descended that same ladder and invited me to the workers’ cafeteria. He poured me a fresh cup of the elixir I so desperately craved. Of course, I expressed my deepest gratitude, and after chit-chatting for a few minutes, I promised Carlos that no matter what I decided to write, I’d be sure to mention his kindness.

Thanks, Carlos. As is often the case, God is gracious to me through others. Sometimes, something as simple as a cup of coffee and a moment of kindly conversation is the glorious proof. And now, on to something else.

At the present moment, it would seem I’m sitting not all that far from where the character Richard Collier slept while trying to meet his love interest, Elise McKenna, in the film Somewhere in Time. Christopher Reeve played Collier. Jayne Seymour was Elise. I’ve seen the movie and appreciate both actors. This being my first visit to the Grand Hotel, I can see why the filmmakers chose the location. Few places compare, especially when displaying the reverence that tradition is due. The Grand Hotel is a moment in time no longer accessible yet seemingly still visible.

Men are not called guys or bros but gentlemen. Women are nothing less than ladies. In stride with these standards, there are rules. The rules maintain while at the same time catechizing. Gentlemen or ladies are forbidden from classless attire. None may don mid-riff baring tops or sleeveless shirts. Why? Because modesty is extolled, and public displays of sensuality are dissuaded. Sweatpants and cut-off shorts will see you sent to your room to change. For what reason? Because self-attentiveness and its production are lauded, while slothfulness should be no respectable person’s way. After the 6:30 p.m. hour, what was politely casual must reach even higher. In all corners of the hotel, suits and dresses are expected for adults. Any attending children must wear the same.

I’m fascinated by this. For a guy like me who sometimes spends his energy writing and speaking about things relative to these lessons, it’s just short of magical. It makes me wonder how the hotel’s management has continued to get away with doing it for so long, especially since such practices are contrary to the nature of the world in which we currently live. Few get away with telling anyone else what they can or cannot do. All are free to be, do, and say whatever they want without consequence. Moreover, men are not men, let alone gentlemen. They’re women. Women are not women, let alone ladies. They’re men. Few are willing to contest this. Even fewer, if any, are eager to pinpoint morality’s demonstration genuinely. A young girl’s parents smile as she receives her diploma wearing little more than a stripper’s dress. A young man’s parents shout expletive-adorned congratulations from the audience to their son. Show more skin, not less. Say whatever you want as loudly as you want. Be a self-serving individual, not an others-minded part of a community.

Indeed, the Grand Hotel is somewhere else in time. Or maybe a completely different world altogether.

In a roundabout way, it reminds me of what I’m seeing happen to northern Michigan’s trees as summer turns the corner into autumn and eventually winter. It won’t be long before Michiganders will see with their own eyes a divided cosmos. One day, we’ll climb into our beds, the scenery beyond our chilly windowpanes completely unobstructed. The next, we’ll awaken to a thickly covered landscape blanketed in drifting snow, the phone ringing for some of us with school cancellation news.

It’ll be like crossing from one world to another, both having different rules.

Inherent to winter’s rules is the awareness that while the season can be beautiful, it can also be perilous. Mindful of these dangers, a winter’s drive can be calming. Playing in the snow can be joyful. A walk in the woods can be refreshing. Doing any of these things as though the rules don’t apply—as though one’s preferences will be best—could cause terrible things to happen. A winter’s drive at 80 miles per hour could kill you and others around you. Building a snowman with your bare hands could result in frostbite and permanent nerve damage. Walking through the wintry woods wearing your favorite summer clothes could end in frozen death. For anyone denying these realities, a person willing to step up and enforce rules is an asset.

I experienced a combative conversation a few weeks ago. The person called more or less to let me know what a horrible person I was for saying publicly that certain behaviors were indeed sinful. According to this person, I had no right to impose morality on anyone, especially since I am just as imperfect as everyone else. This is a typical argument many make and often aim at the clergy. She went on to say that she’d never think of imposing morality on anyone. I asked her if such thinking applied in her home with her children. She stuttered a little at that point. She did everything she could to make “yes” her answer, explaining how she raised them to be free thinkers unbound by legalistic principles. I asked what she would have done if her daughter had come to her, admitting she intended to kill a friend at school. Would she say her daughter was wrong, that killing someone was against the rules? Her answer was one of avoidance: “My daughter would never do that. Because of the way I raised her, she’d know better.”

“So, there is such a thing as ‘better’? What or who established that better standard, and why does it appear to apply to everyone, including you?”

The conversation didn’t proceed much further. I didn’t expect it would, anyway. And by the way, I wasn’t trying to win an argument. There’s no winning in such situations. There’s only giving a faithful witness while enduring. Still, I suppose this came to mind because of what I’ve said here. If we establish our own standards apart from reality, not only will we discover ourselves in conflict with natural law, but we’ll never be able to see beyond ourselves what’s actually true. Perhaps worse, we’ll never know what it’s like to be part of a community held together by that truth—a group naturally built to outlast all others.

Still, there’s another angle to this that comes to mind.

While the rules here in the Grand Hotel’s world do not apply to the mainland’s rules, both are held by the same standards, whether or not they acknowledge it. Summer or winter, right is right, and wrong is wrong. They may look different by context, but they’re rooted in truth, and they are what they are. One day, everyone will realize this. In a sense, it’ll be like the scene I described before. You’ll close your eyes in one world and open them in another. When you do, you’ll realize that human standards never applied in either. Instead, there was all along a deeper standard—God’s standard. It will be the only standard of measurement at that moment. A world of people choosing unbridled sensuality, gender confusion, and so many other dreadful standards will finally discover if they were right in their cause. They’ll learn, in a sense, if the Grand Hotel’s rules were better than Walmart’s.

Thankfully, we have Christ. He’s the hope we have for that inevitable day. He’s the One who forgives us of anything that might make that day a dreadful one (Luke 21:28). He’s also the One who gives His Holy Spirit so that we are remade into those who desire His will and ways, not our own (Romans 5:5; Galatians 5:22-23). That’s important. When I want what I want, the Spirit fights that fleshly inclination, making it so that I prefer instead what Christ wants. I want what Christ wants because, by faith, I know it will always be better. It is a higher standard. According to Saint James, it’s the law of liberty (James 1:18,25-27)—the freedom from sin’s guilt and the liberty to live according to God’s way of righteousness (2 Corinthians 3:17). This is a change in eternity’s conversation. In Christ, I don’t have to keep God’s rules perfectly to save myself. Jesus did that. But now, through faith in Him, I want to keep his rules. I know they’re good. In fact, I know they’re not just better but the best.